Week 1️⃣ 4️⃣

Public Art

🔊 Audio

📜 Show transcript

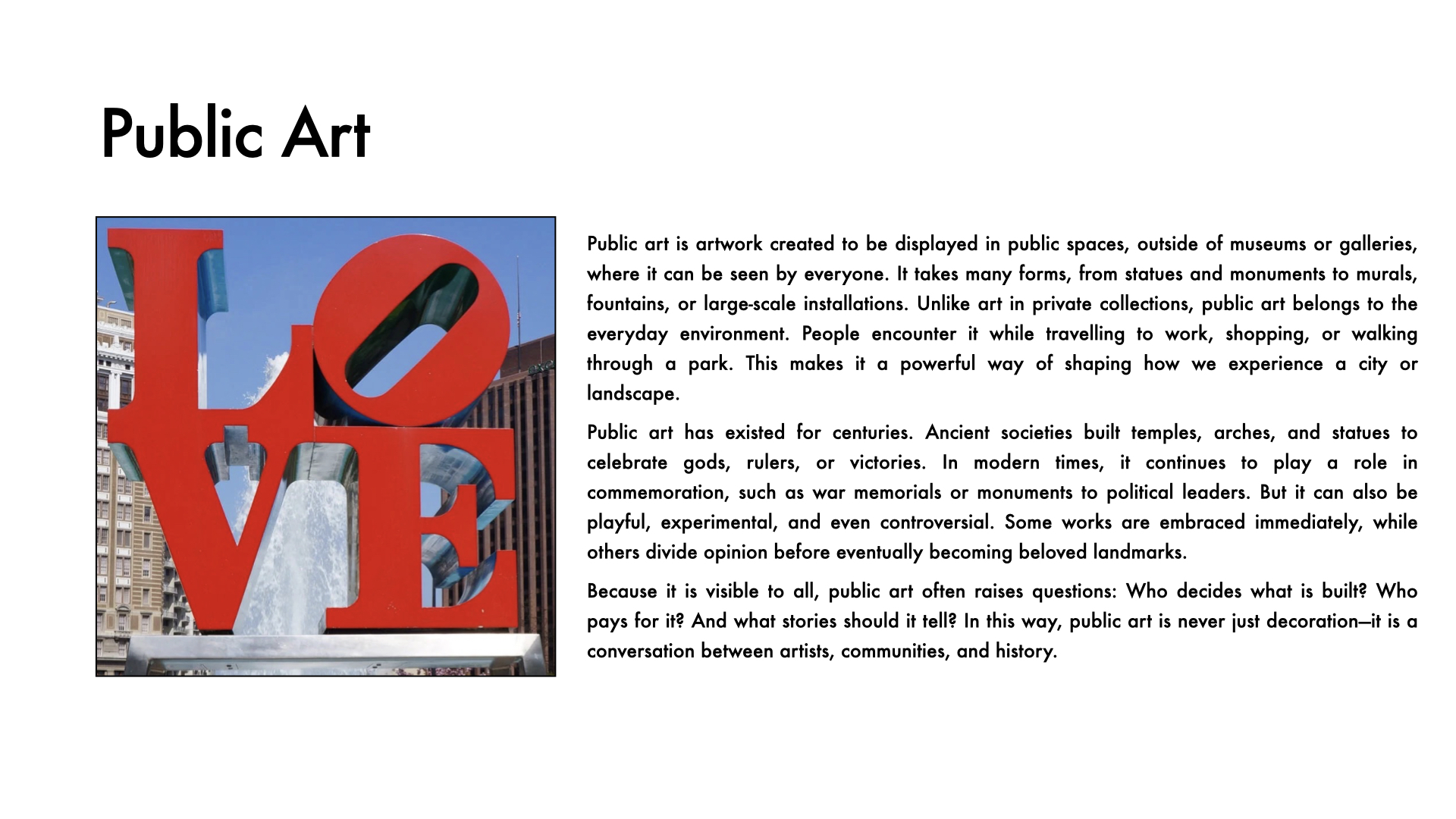

Public art is artwork placed in spaces where everyone can see it, not just in museums or galleries. It can be large or small, temporary or permanent, traditional or experimental. Because it is always visible, public art often creates discussion. Some works become famous and loved, while others are ignored or even disliked. But all of them are part of how a community presents itself and remembers its history.

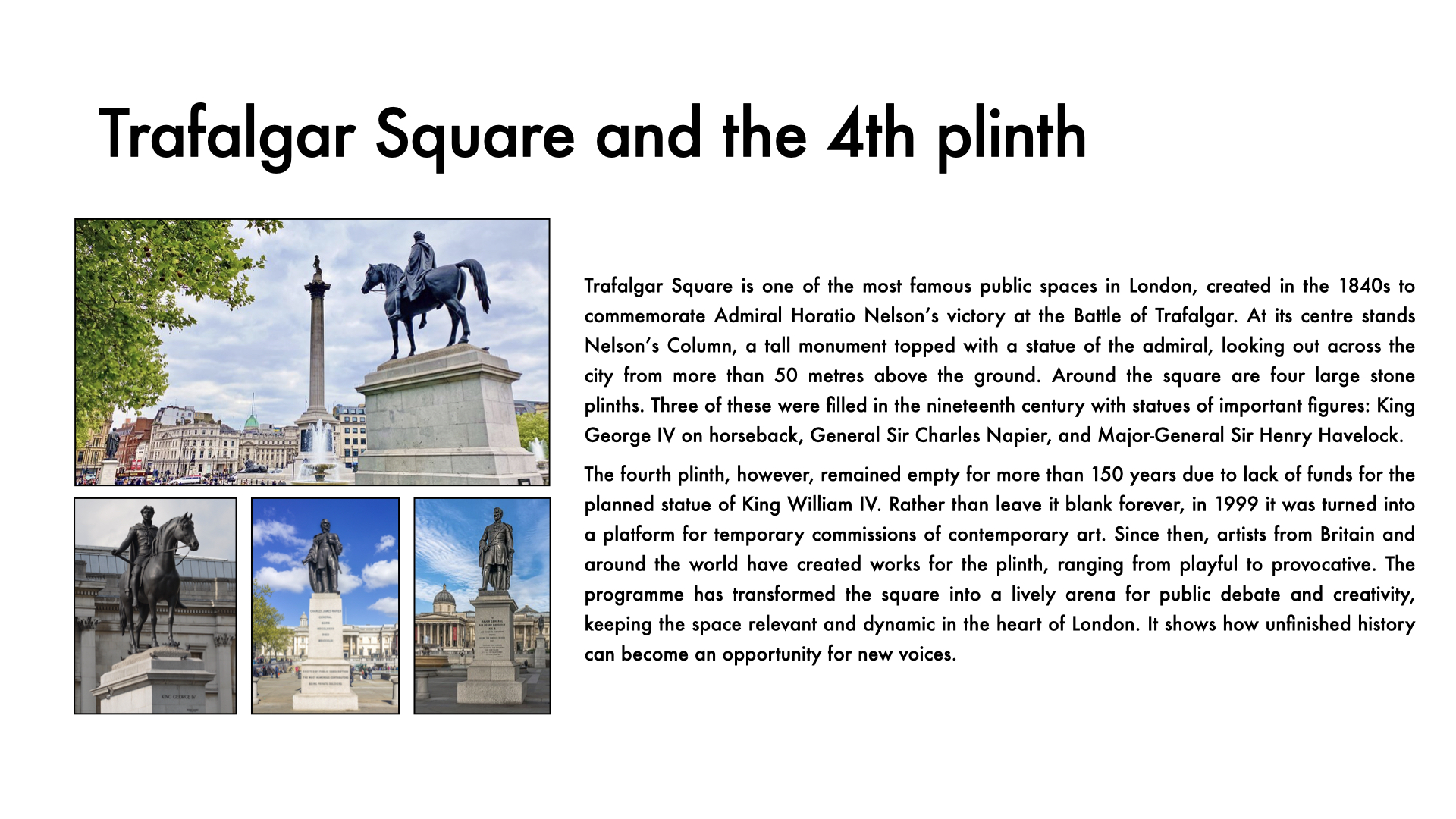

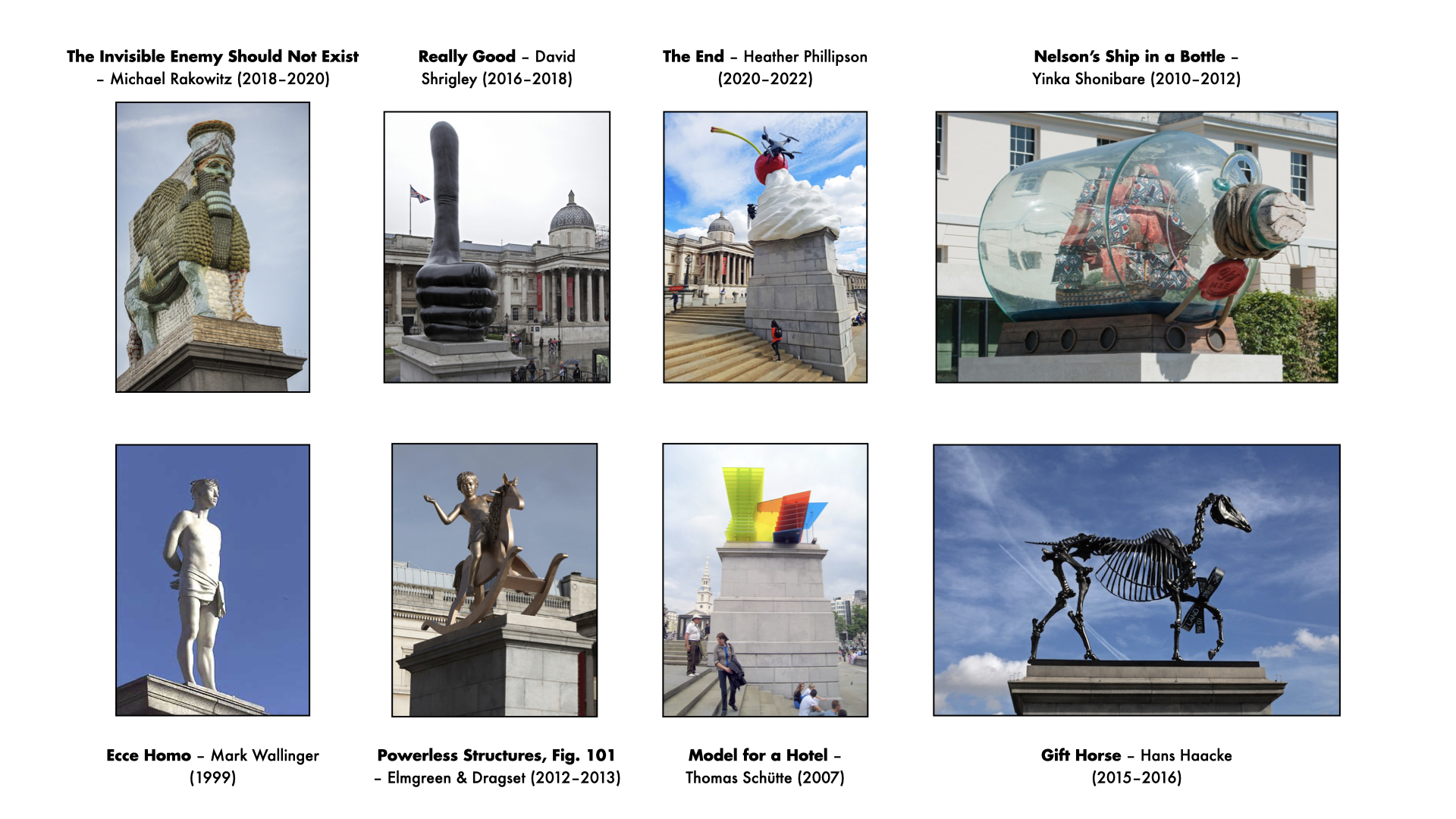

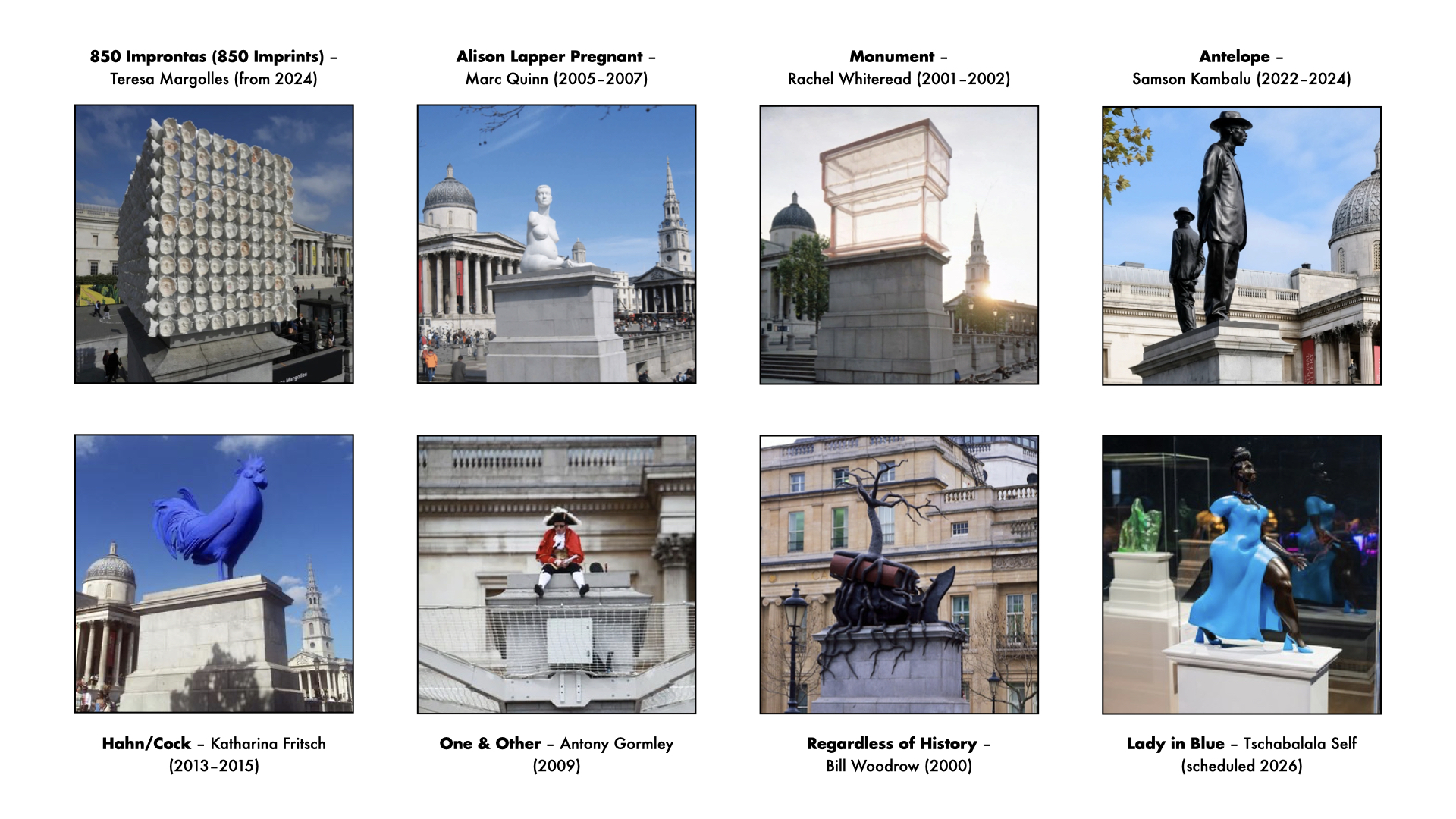

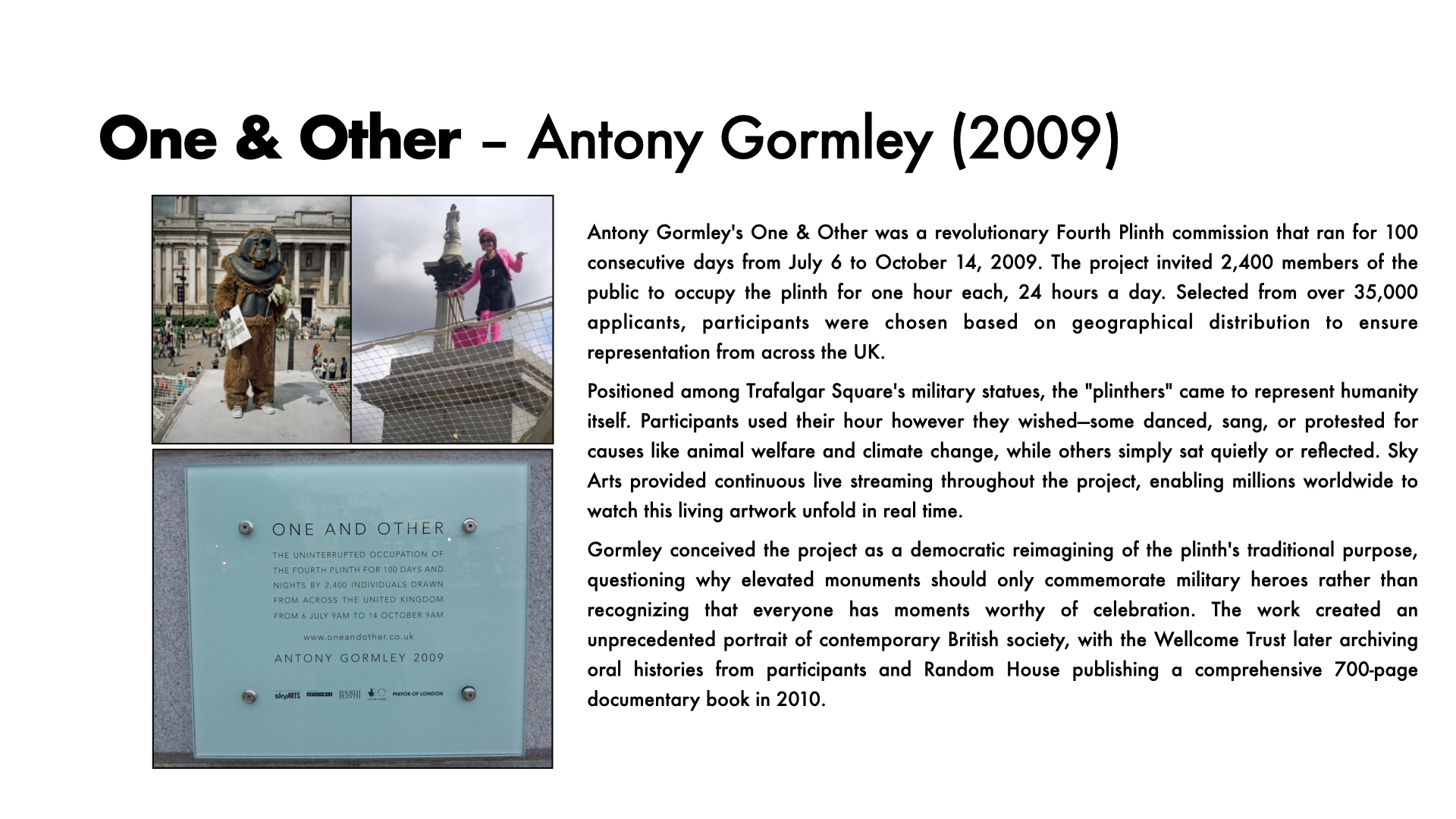

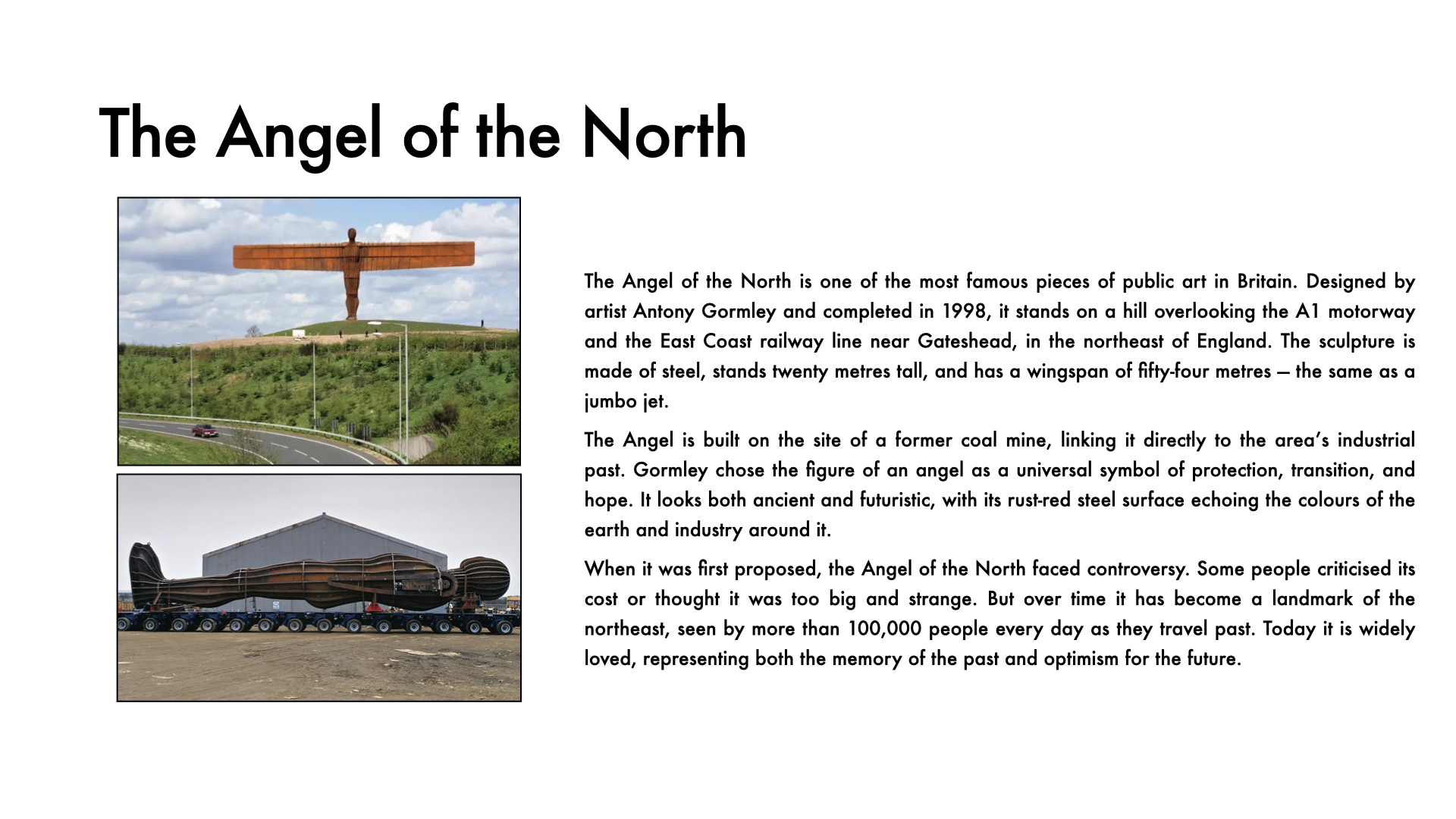

One of the most interesting examples is the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London. The plinth was originally meant to hold a statue of a king, but it remained empty for more than a century. In 1999 it became a platform for temporary artworks. Every few years a new piece is chosen. Some of these sculptures are serious, others playful, but all of them make people stop and think about what kind of art belongs in such an important space.In the north of England, Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North shows how a sculpture can move from controversy to acceptance. Completed in 1998, the Angel is made from steel, stands twenty metres tall, and has a wingspan of fifty-four metres—the same as a jumbo jet. Gormley chose the image of an angel as a universal symbol of protection and transition, watching over the former coal mining site where it now stands. More than one hundred thousand people see the Angel every day as they travel past on the A1 motorway or by train. At first many thought it was too large and strange, but now it is one of the most recognisable landmarks in Britain.

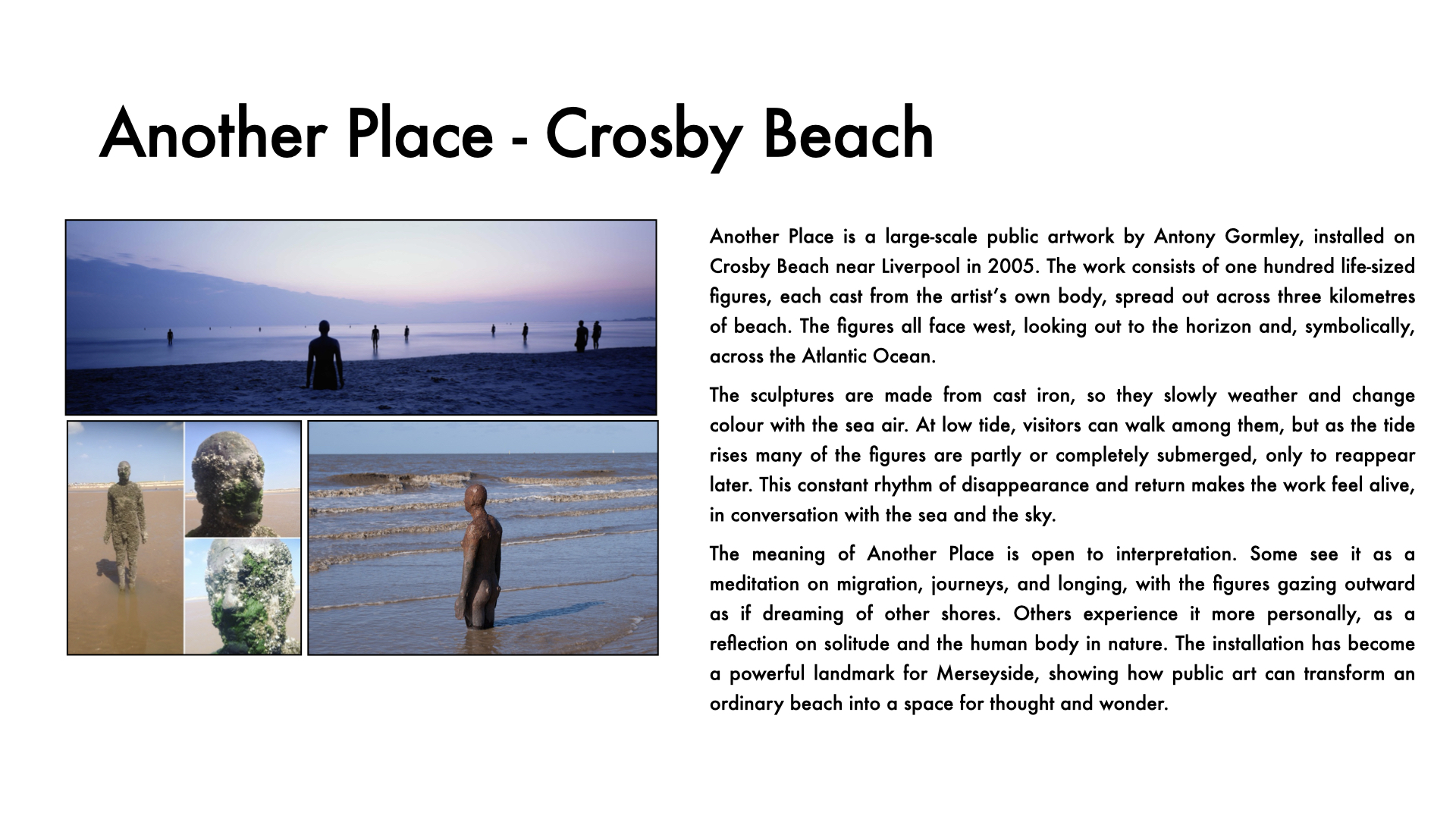

Gormley is also the artist behind Another Place on Crosby Beach near Liverpool. This work is made of one hundred iron figures, each cast from the artist’s own body. They are spread out across the sand, facing west towards the horizon. As the tide comes in and out, the figures are sometimes partly under water and then revealed again, so the artwork seems to breathe with the sea. Many people see the figures as a meditation on migration, on journeys across water, and on the idea of standing at the edge of one world while looking towards another. Facing the Atlantic, they suggest the dream of crossing oceans, even the idea of leaving for America.

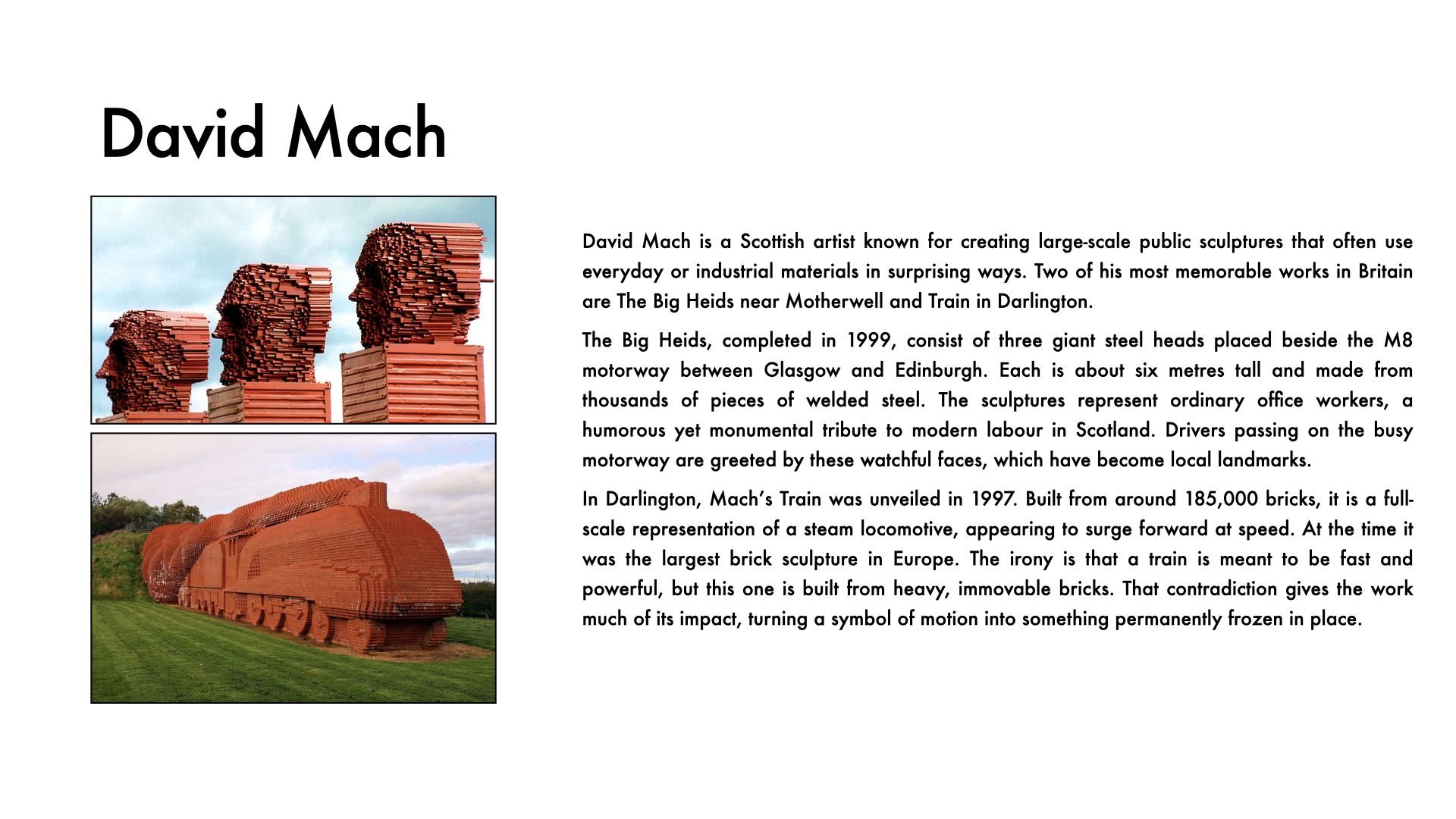

Other artists, such as David Mach, have also contributed major public artworks. His Train in Darlington, made from more than one hundred and eighty thousand bricks, is a full-sized locomotive. The irony is striking: a train should be fast and powerful, but this one is built from heavy brick and can never move. The joke is part of what makes it memorable. Mach is also the creator of the Big Heids in Motherwell, three giant heads made from steel, reminding people of Scotland’s industrial past.

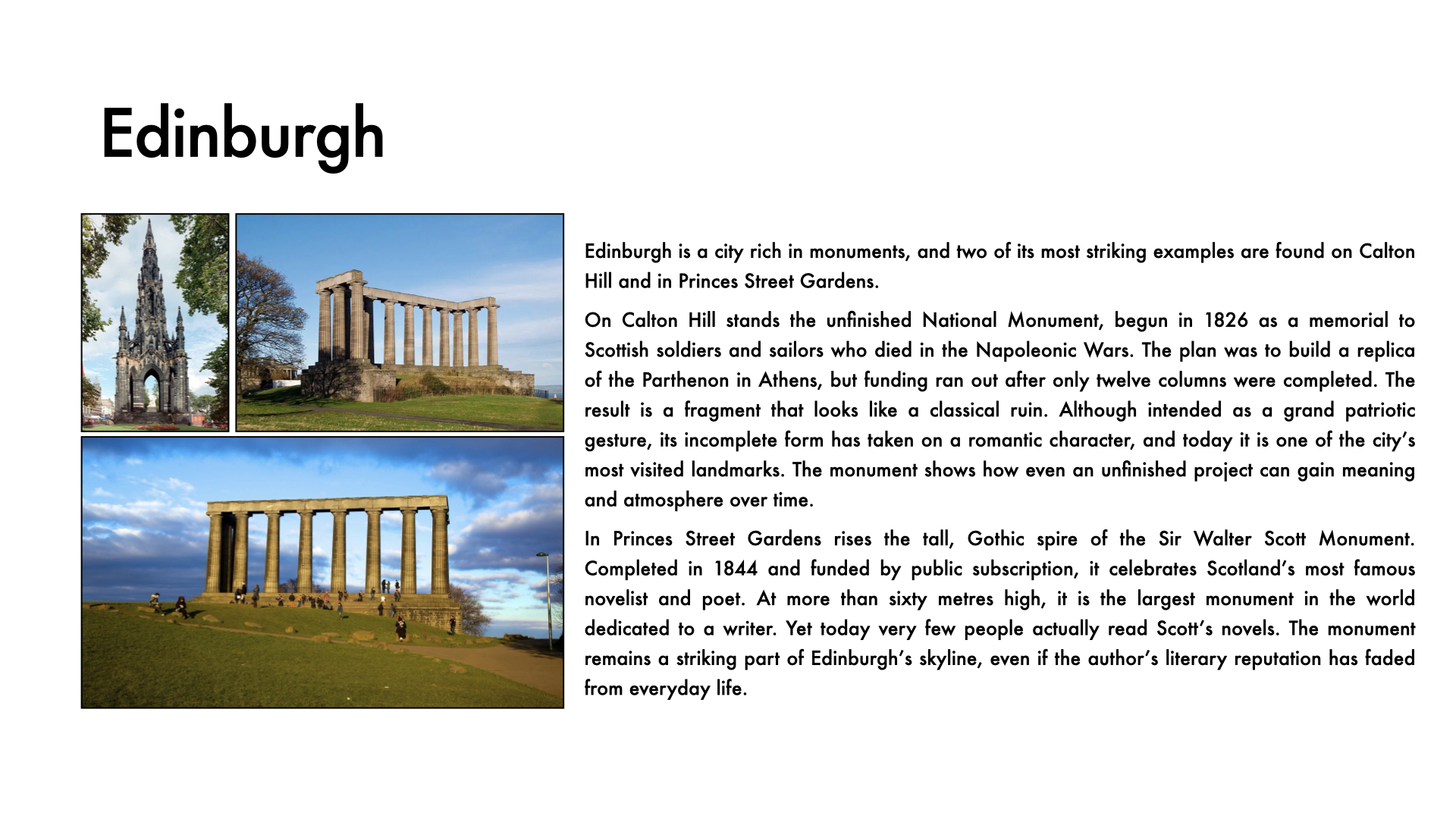

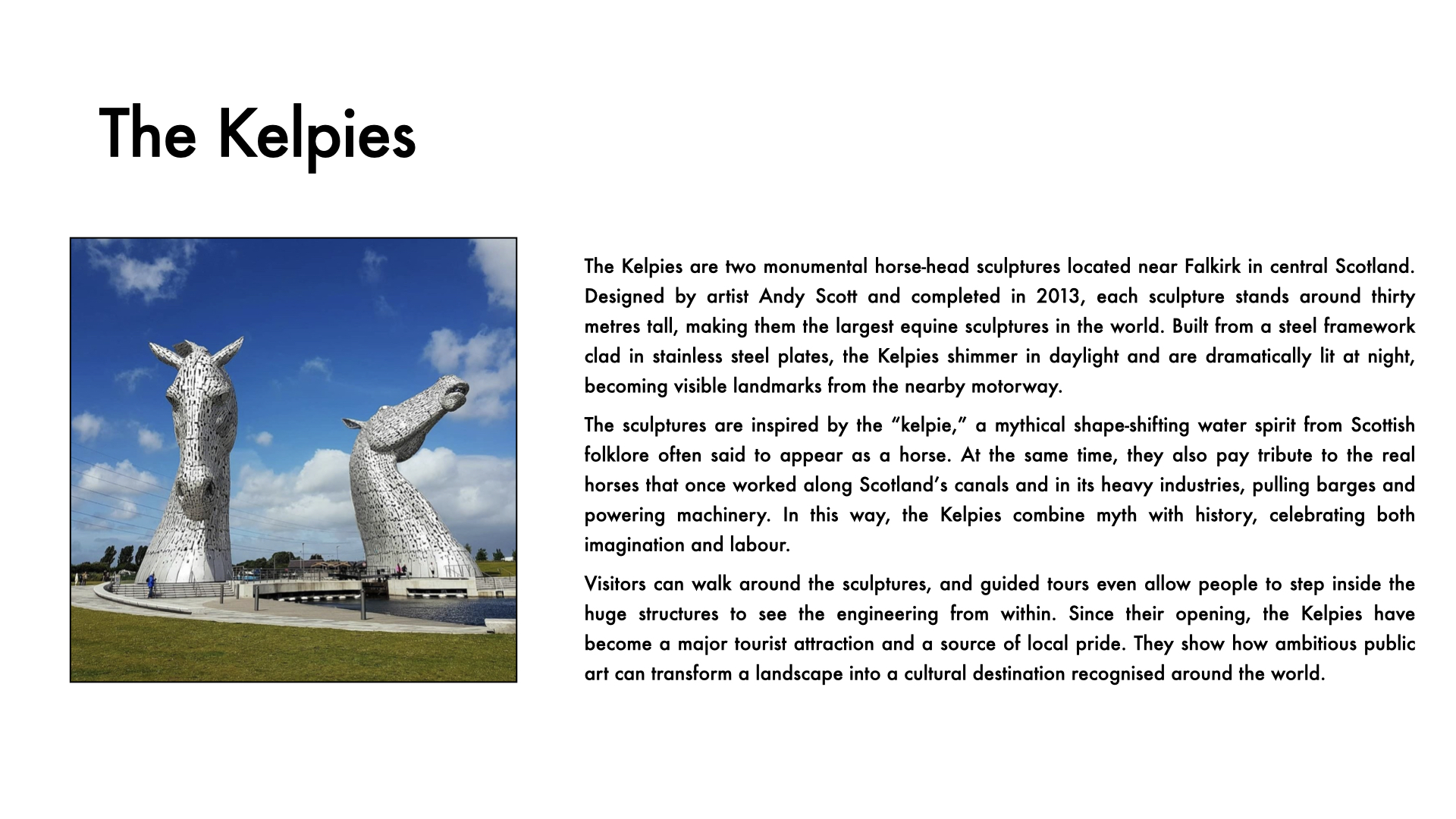

Scotland has further landmarks of public art. The Kelpies near Falkirk are two enormous horse heads, thirty metres high, inspired by both legend and industry. In Edinburgh, the National Monument on Calton Hill was left unfinished when funds ran out, turning it into a romantic ruin. Close by stands the Gothic Scott Monument, built to celebrate Sir Walter Scott, showing how seriously literature was once honoured—even if very few people today read his novels.

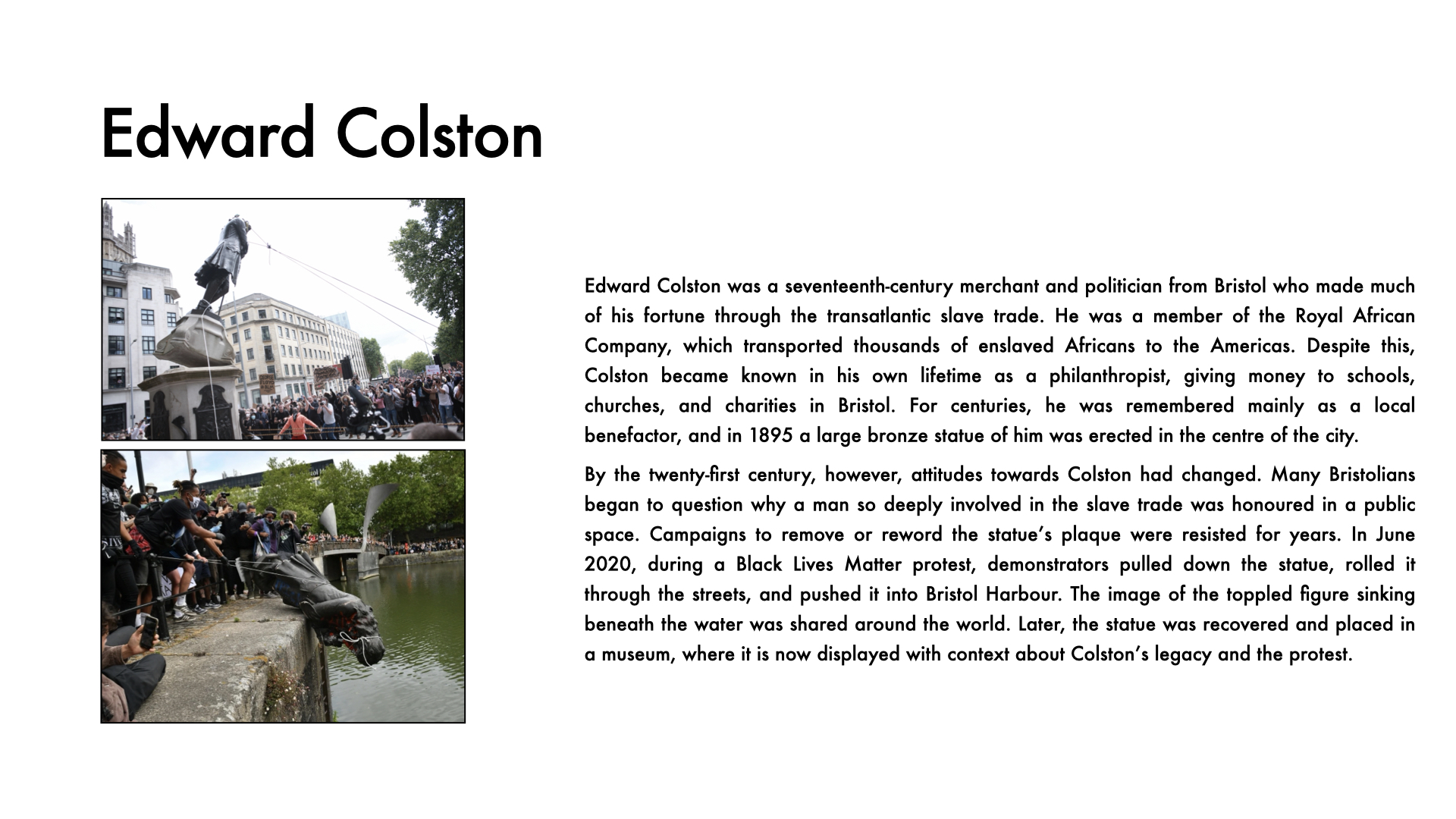

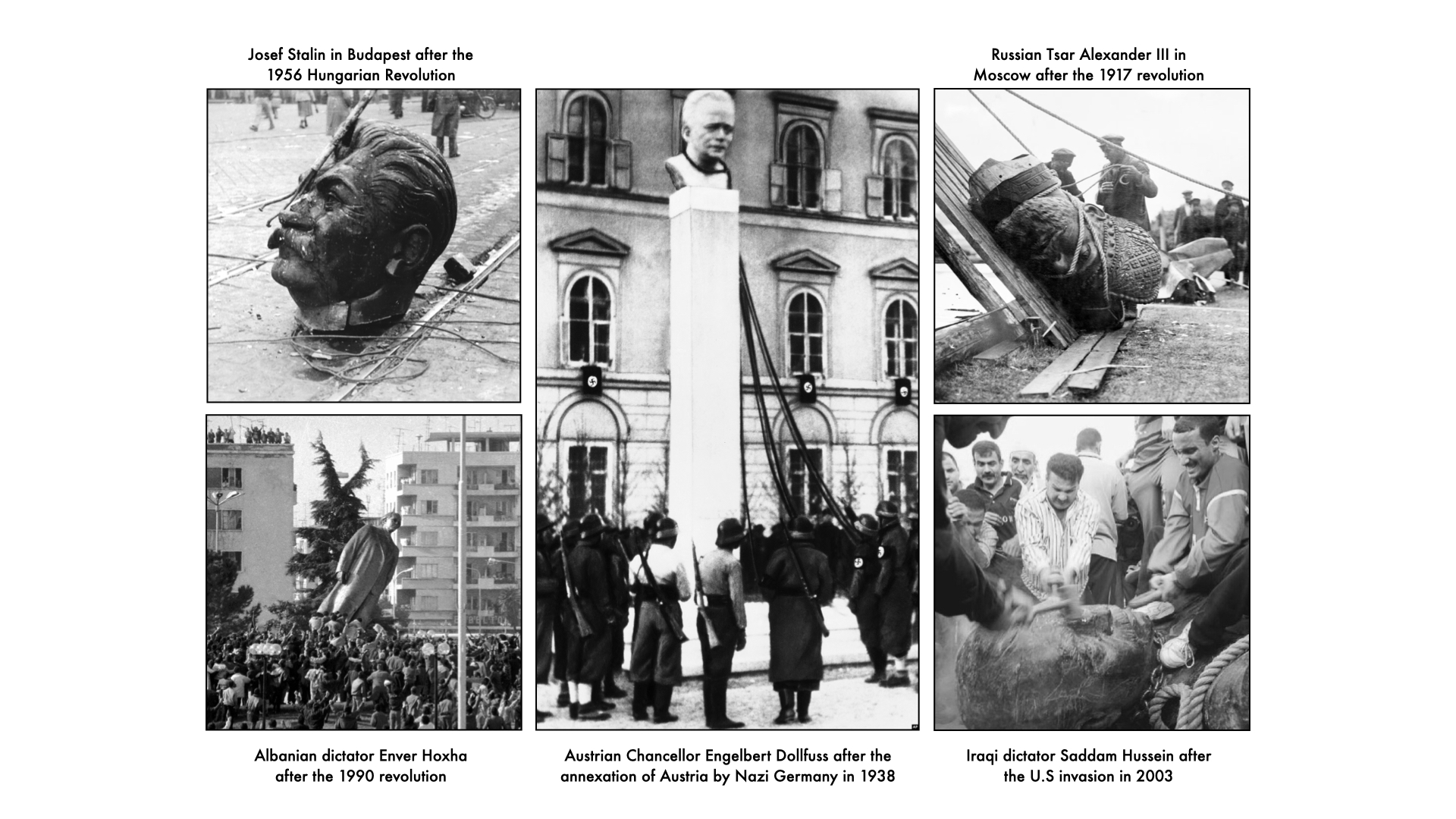

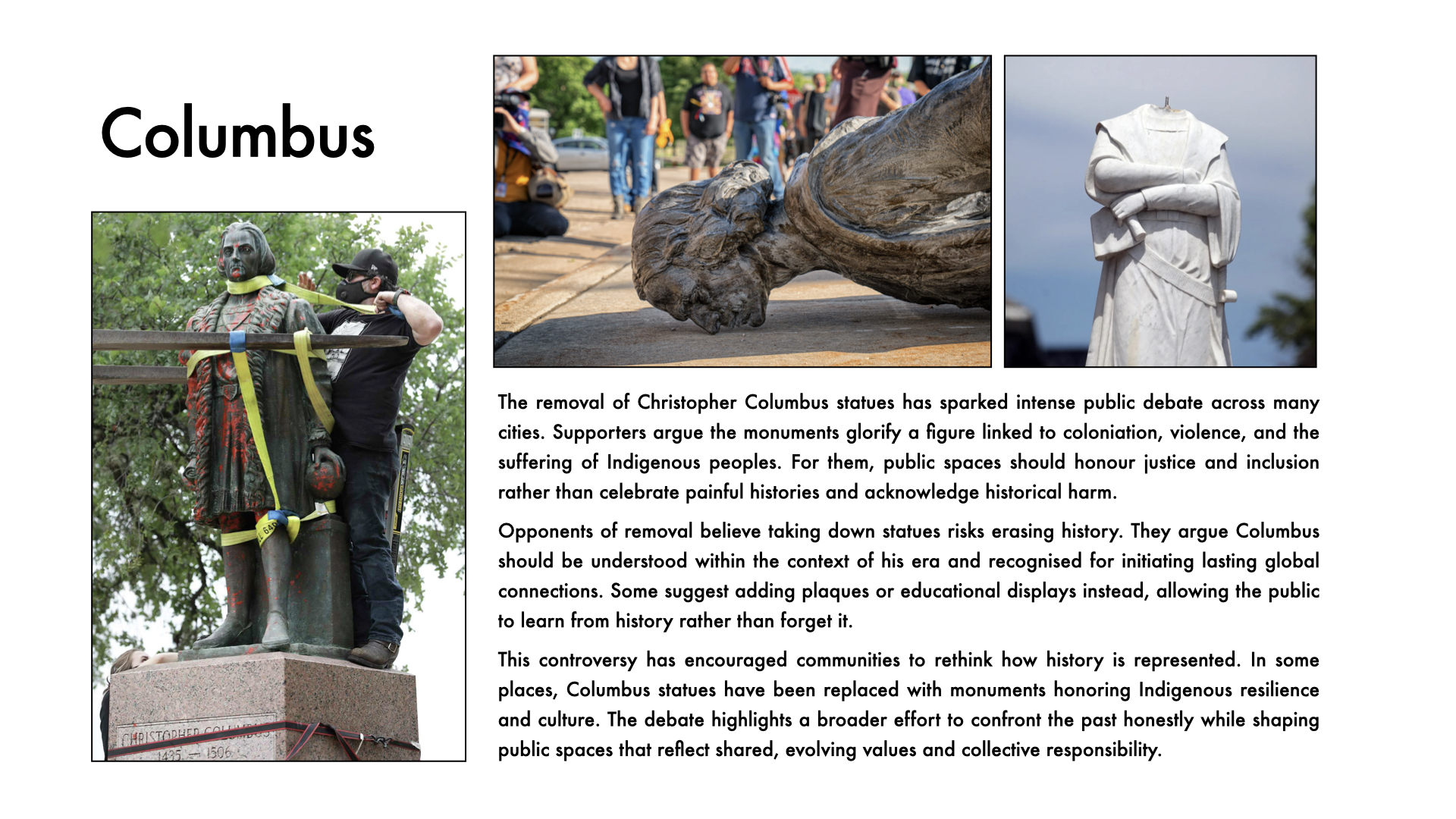

Public art is easy to walk past and ignore, especially statues of old leaders and generals. But sometimes the opposite happens. In Bristol, the statue of Edward Colston, a man linked to the slave trade, was pulled down during a protest and thrown into the harbour. Such moments show that public art is not fixed forever. Monuments can be questioned, moved, or destroyed when societies change their values. Together, these works remind us that public art tells us not only about the past, but also about how people in the present choose to remember it.

📽️ Slideshow

📺 Video

🔑 Key Vocabulary

- Abstract – Art that does not try to represent real objects or people in a realistic way

- Commission – When an artist is formally asked and paid to create a piece of art

- Commemoration – Remembering and honouring a person or event, often through a monument

- Figurative – Art that clearly shows real objects, people, or animals

- Installation – A large artwork created for a specific space, often involving the whole environment

- Landmark – A building, statue, or feature that is easily recognised and represents a place

- Memorial – A structure that reminds people of someone who has died or an event in history

- Monument – A statue or structure built to honour a person or event

- Plinth – A heavy base or block on which a statue or sculpture stands

- Public art – Art placed in outdoor or public spaces, free for everyone to see

- Sculptor – An artist who makes three-dimensional works of art

- Sculpture – A three-dimensional artwork, often carved, modelled, or constructed

- Site-specific – Artwork designed for one particular place, often linked to its history or surroundings

- Statue – A figure of a person or animal made from stone, metal, or other material

- Symbolism – The use of images or forms to represent ideas or qualities beyond the literal

💬 Conversation Questions

- Do you have a favourite statue or monument in your town?

- Have you ever visited a famous piece of public art on holiday?

- Do you usually notice statues in the street, or walk past them without looking?

- Which do you prefer: modern abstract sculptures or traditional statues?

- Do you think public art should always be beautiful, or is it okay if it is strange?

- Would you like to have a big sculpture near your home? Why or why not?

- Who do you think should decide what kind of public art is made?

- Do you think public money should be used to pay for monuments and sculptures?

- What happens if people disagree about a statue or monument? How should the city respond?

- Some old statues are ignored because no one remembers the person anymore. Should they be removed?

- What do you think about removing statues of people with controversial histories?

- Can a piece of public art change the image of a whole city or region? Give an example.

- Is it more important for public art to celebrate the past, or to say something about the present?

- Do you think temporary works, like those on the Fourth Plinth, are more interesting than permanent ones?

- If your town commissioned a new sculpture, what would you suggest and where would it go?