Week 1️⃣ 6️⃣

Affordance

🔊 Audio

📜 Show transcript

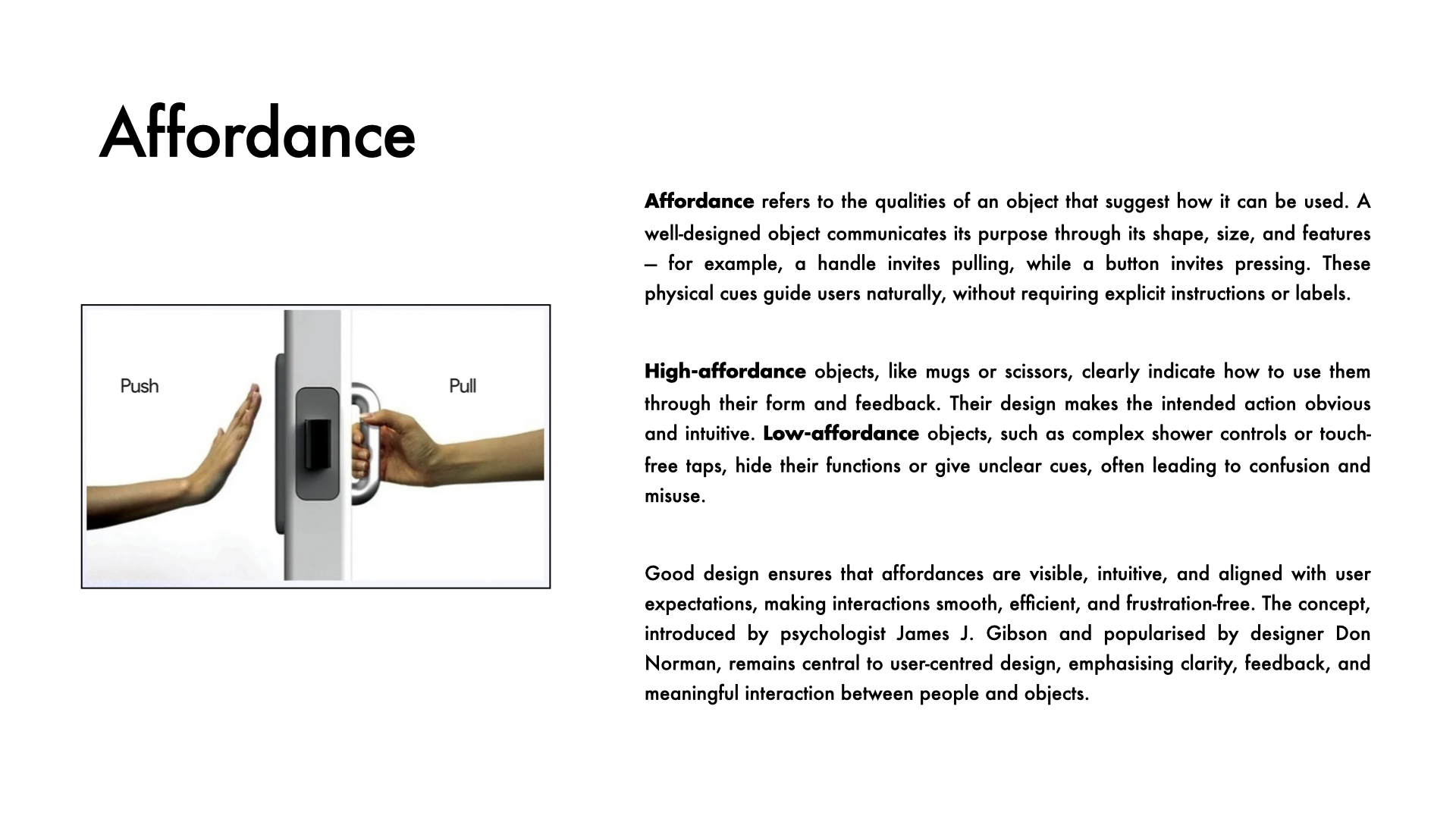

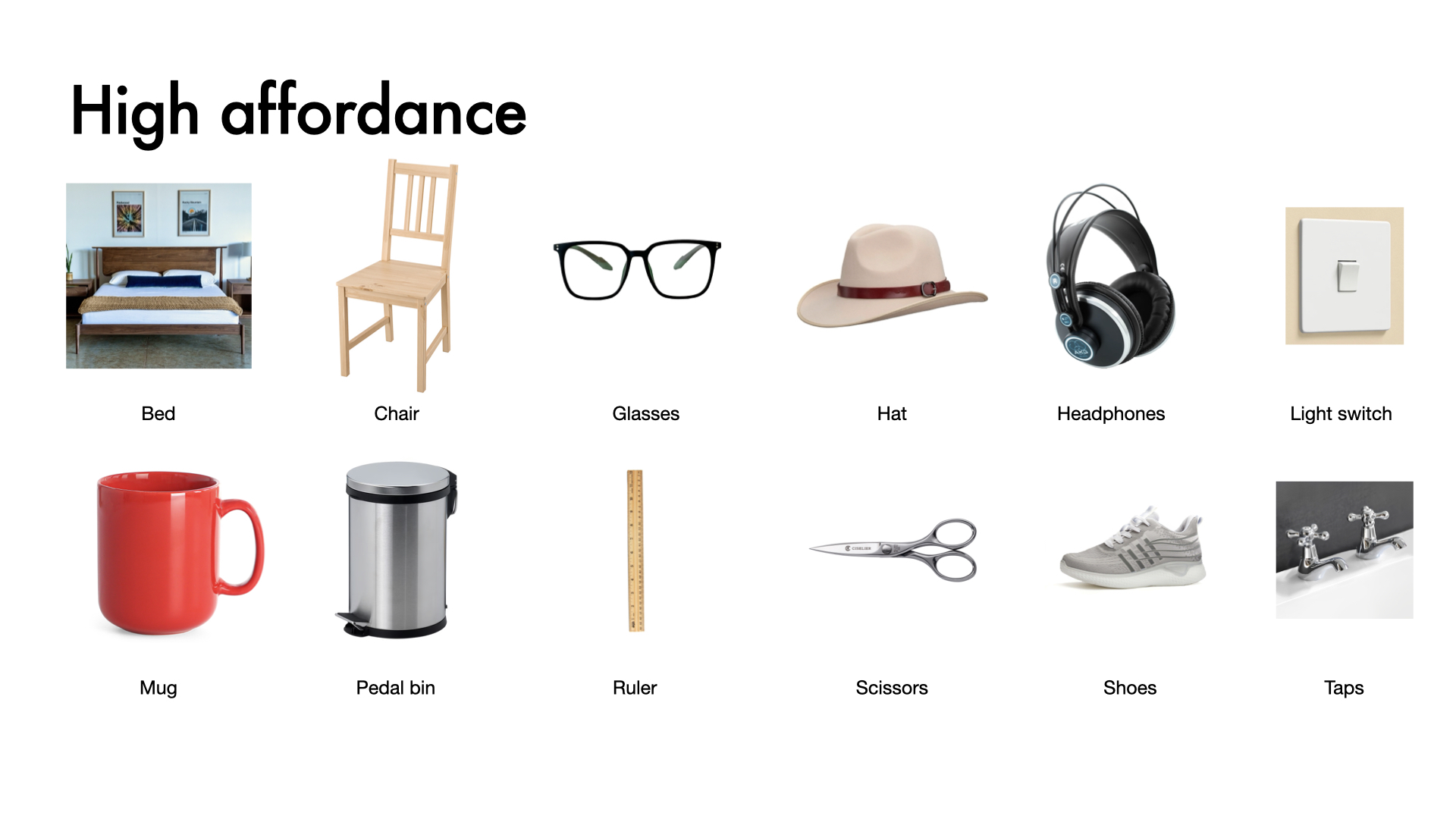

Affordance is a design term that describes the qualities of an object that suggest how it should be used. A really good design tells you what to do just by the way it looks or feels — no instructions needed.

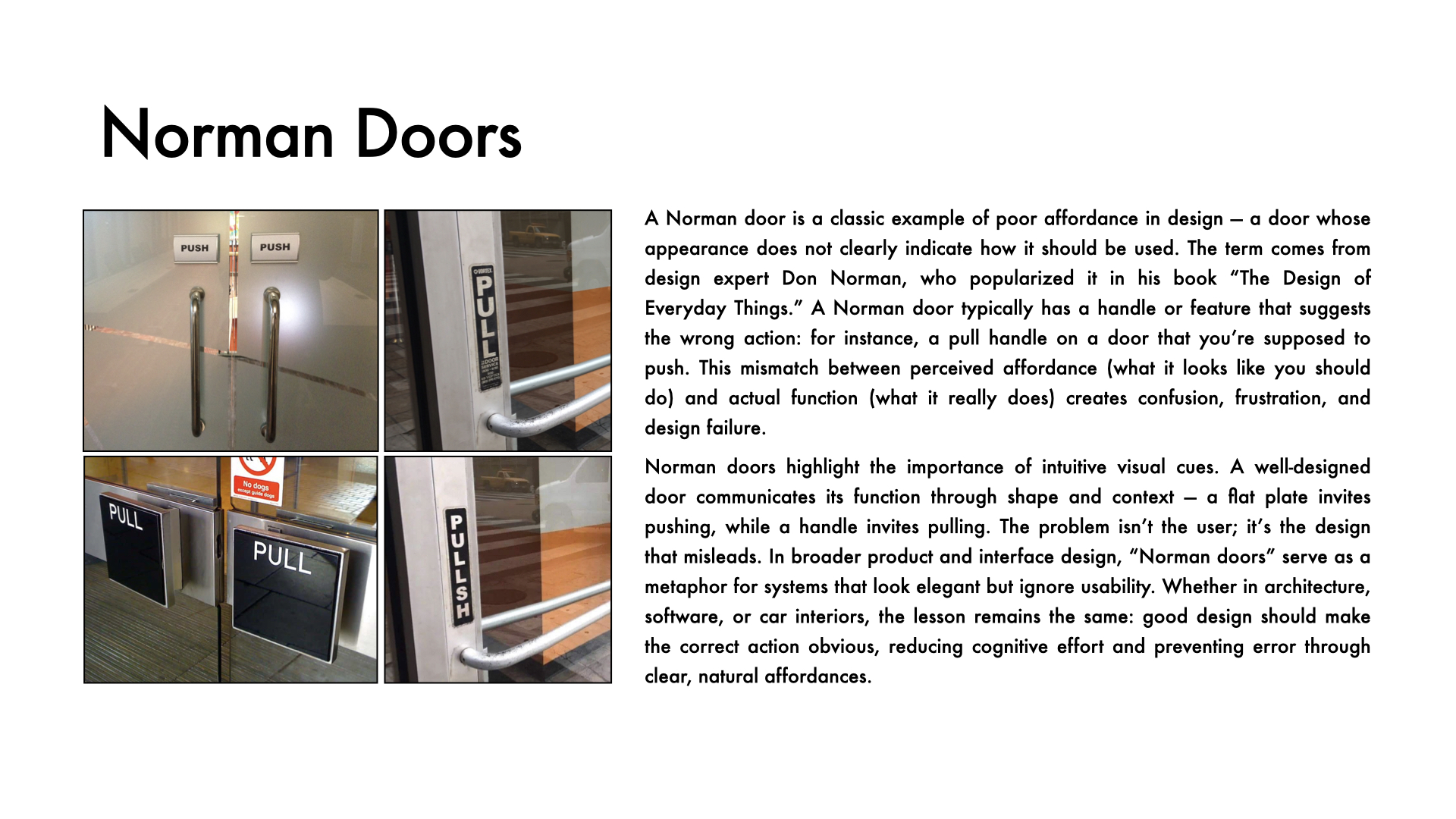

We see affordance everywhere in daily life. A pair of scissors practically explains itself: the loops invite your fingers, the blades invite cutting. The best designs communicate their purpose without words. But when affordance fails, frustration follows. The classic example is the Norman Door, named after designer Don Norman — those doors you pull when you’re meant to push, or push when you’re meant to pull. Their shape sends the wrong signal, so the user feels clumsy, even though it’s really bad design at work.

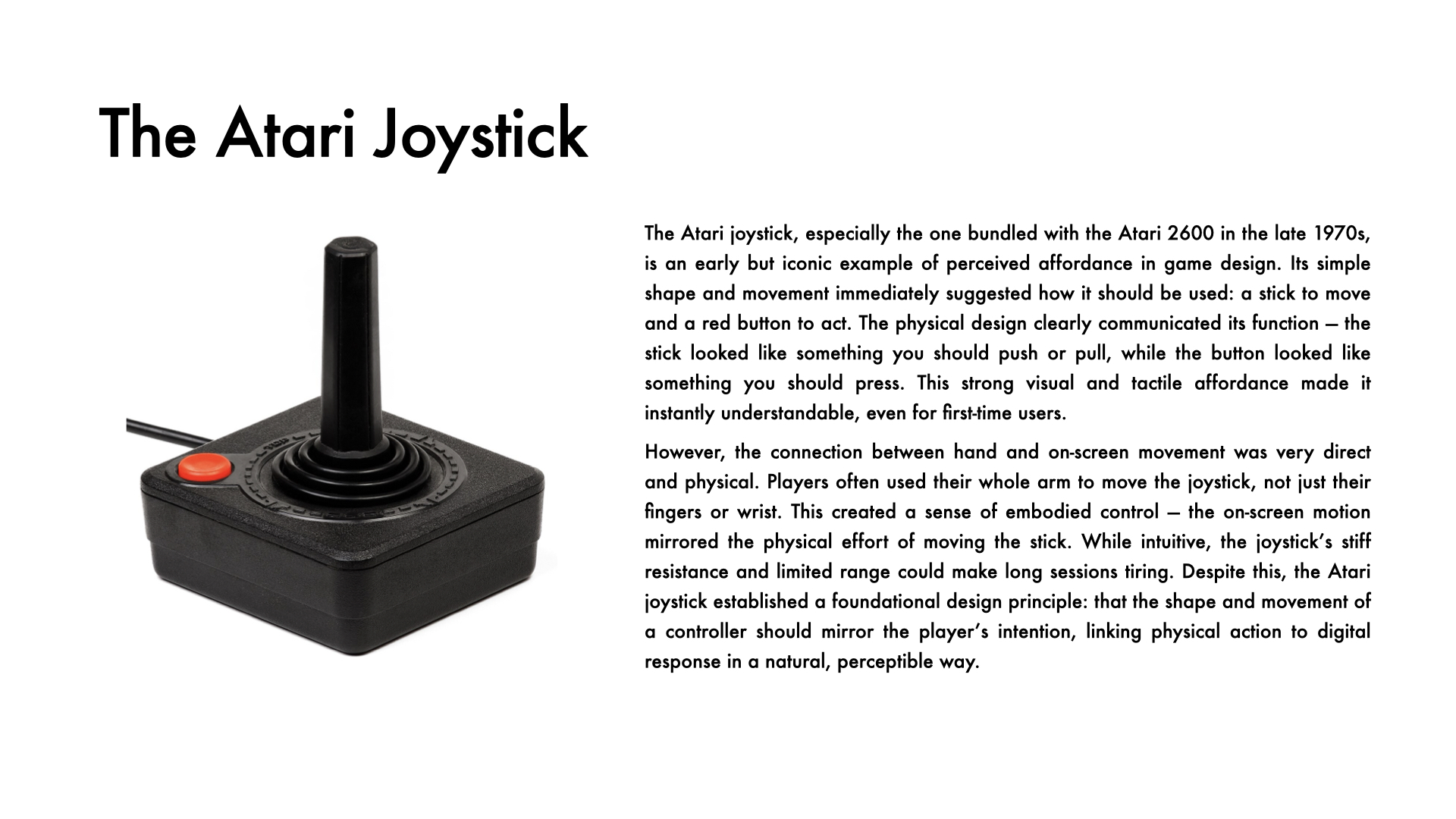

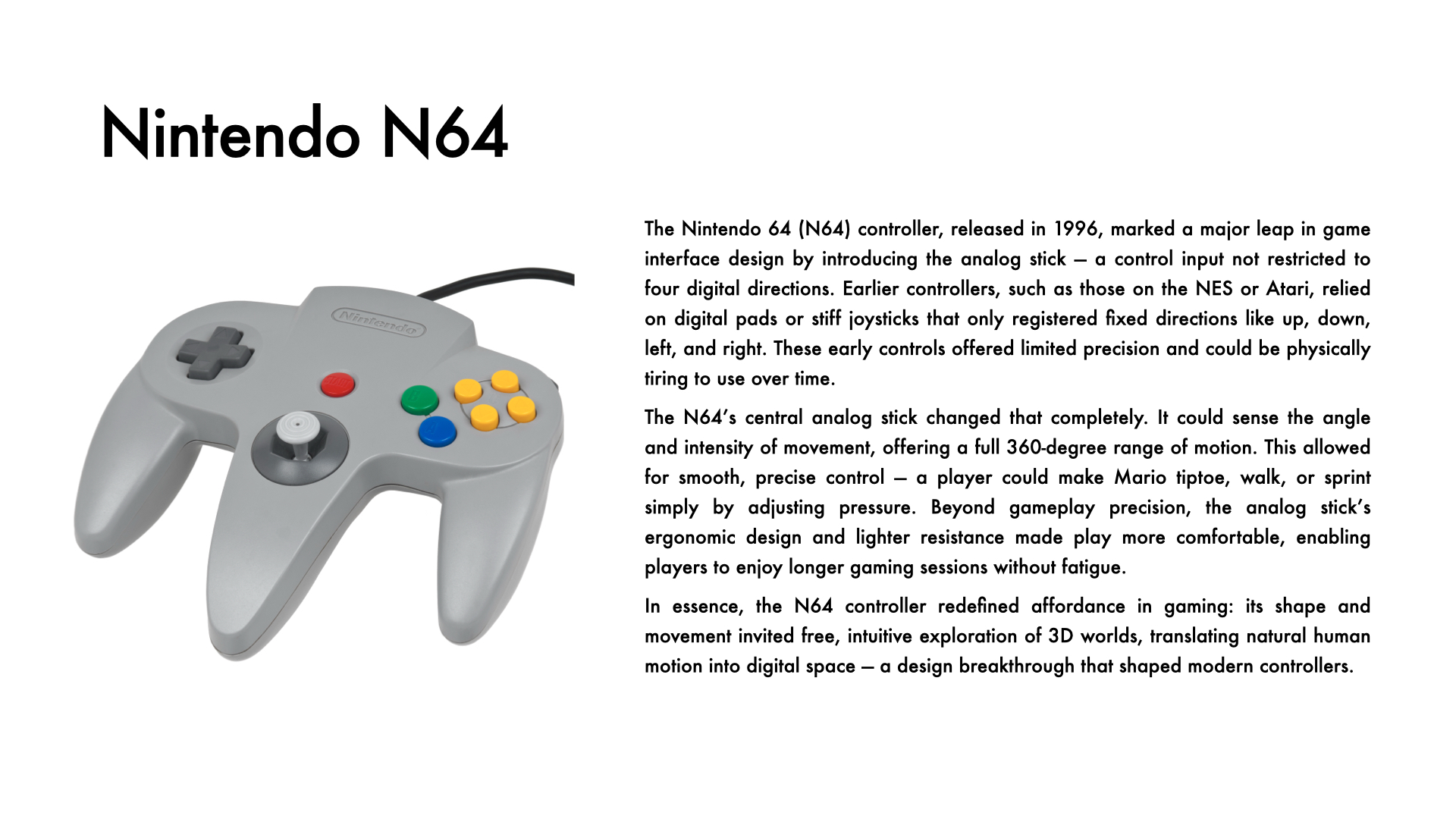

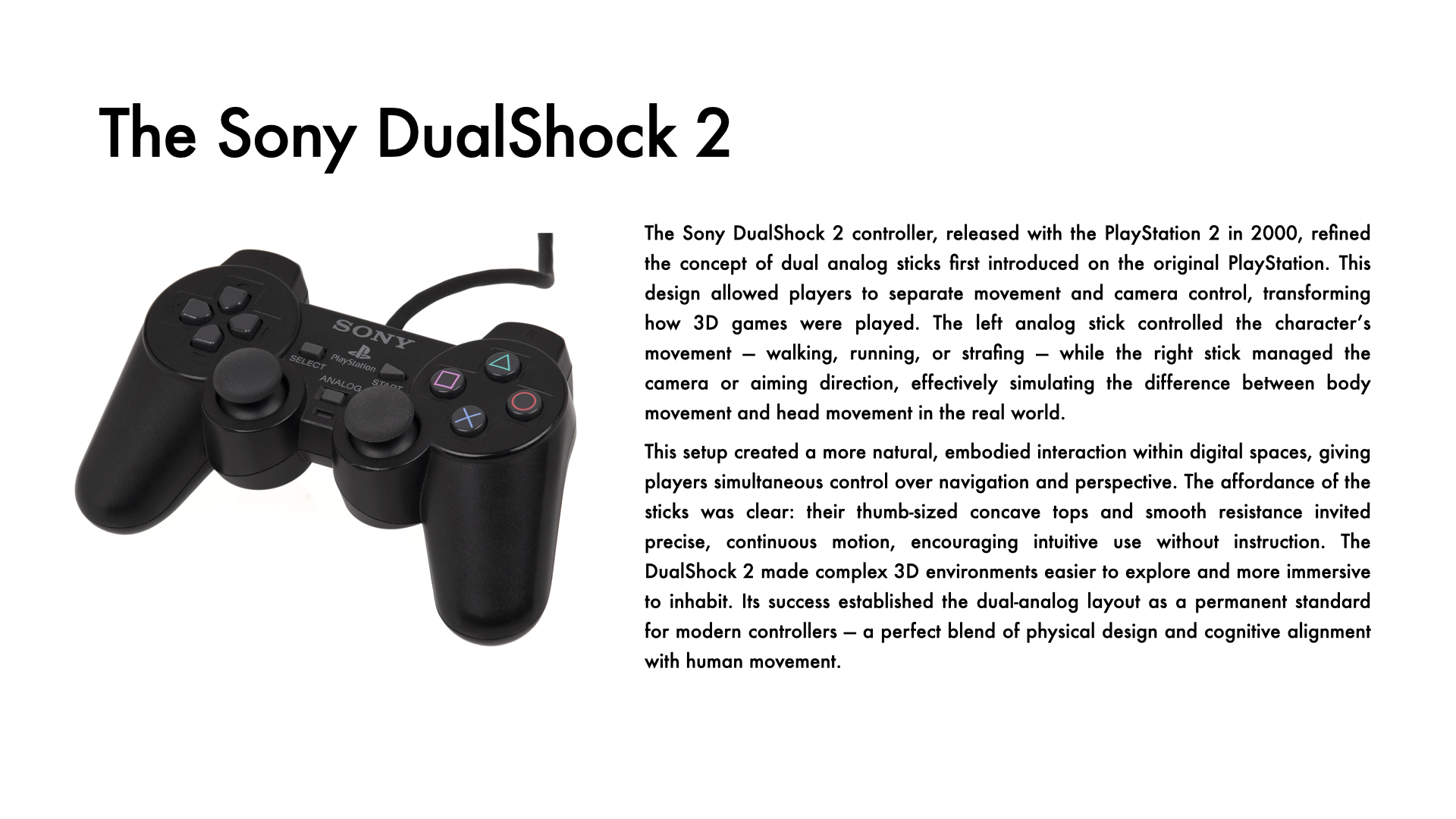

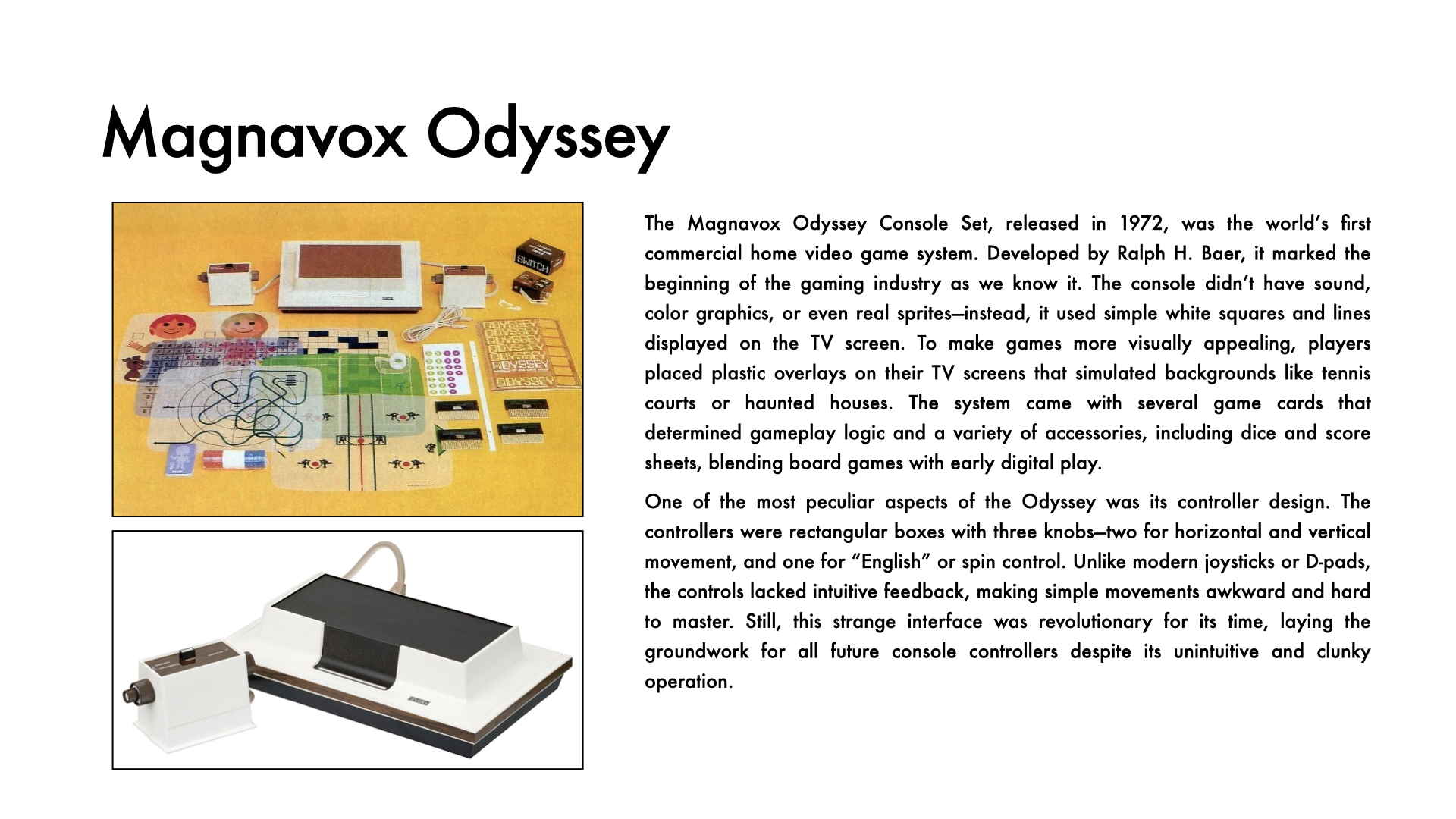

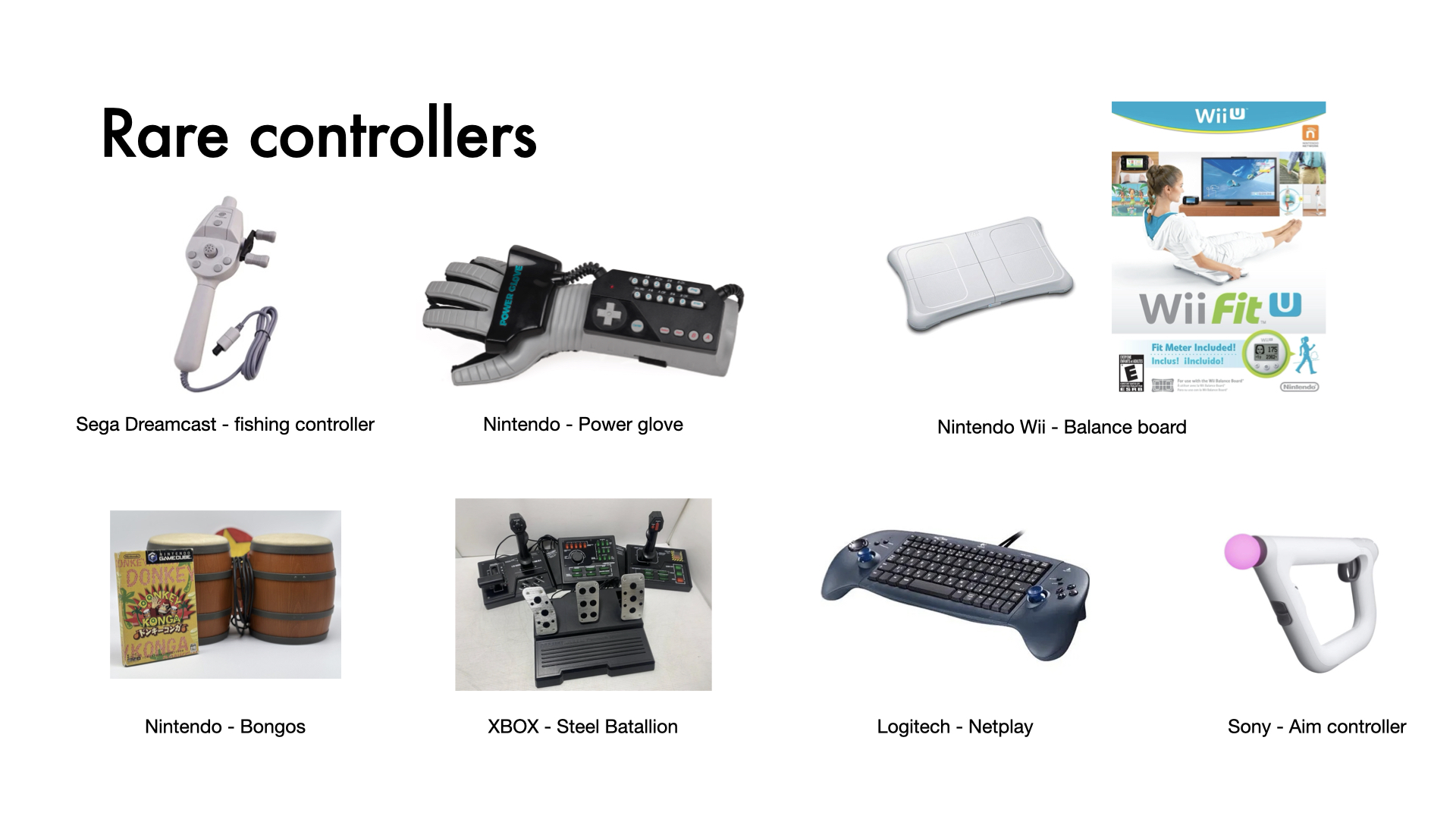

Affordance also drives how we interact with technology. Think of early video game controllers, like the Atari joystick from 1977: push forward to go forward, pull back to reverse — it mirrors the action on screen perfectly. Then came the Nintendo 64 in 1996, with its central analog stick. For the first time, players could move fluidly in 3D space rather than just four directions. That changed again with the PlayStation Dual Analog in 1997, which introduced a second stick — move with your left, look or aim with your right. It separated walking from seeing, giving players independent control of body and perspective — a subtle but revolutionary shift in digital affordance.

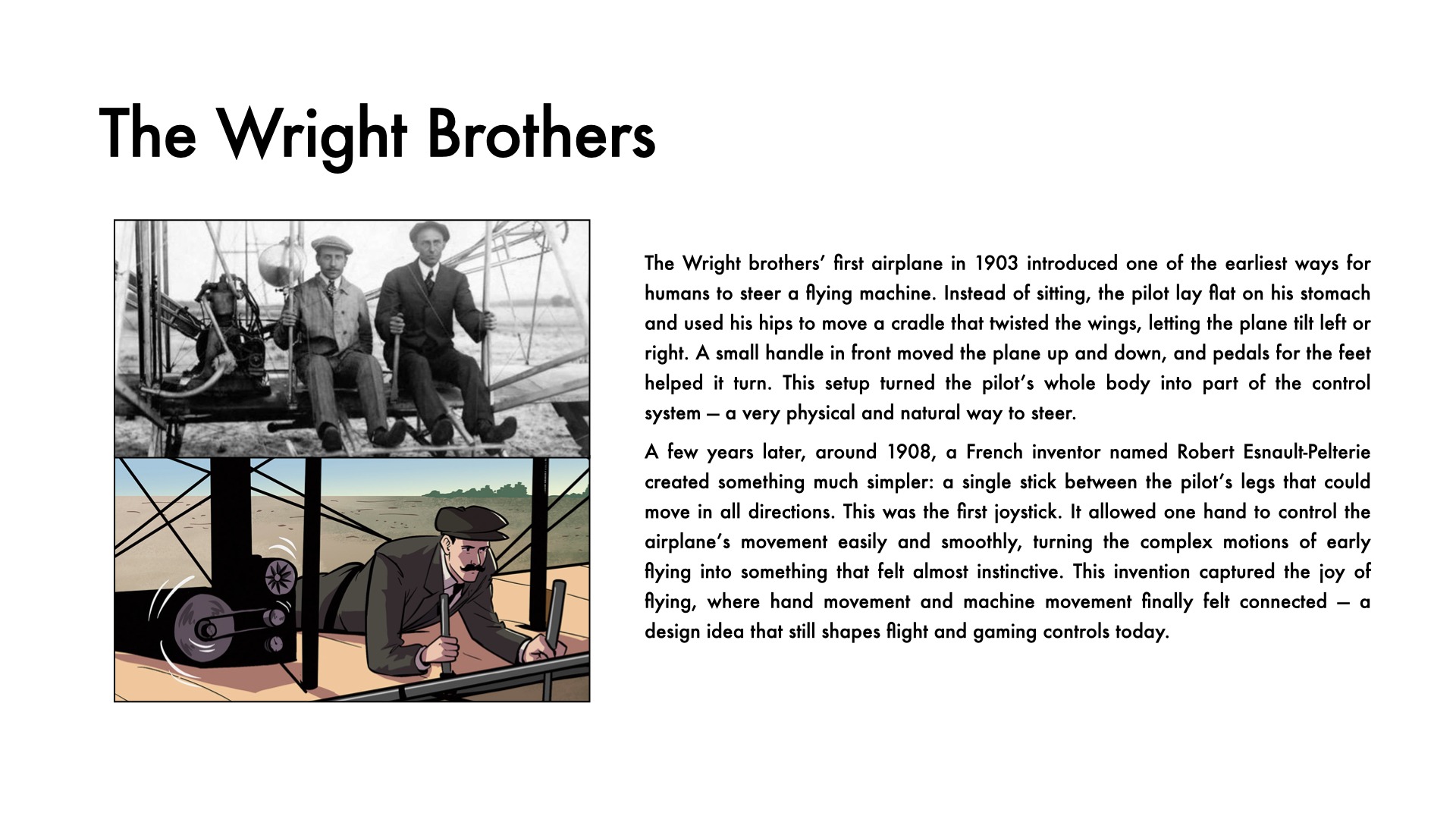

That joystick design actually came from aviation. The Wright Brothers didn’t have one in 1903 — they flew lying on their stomachs, shifting their hips to steer the plane, and pulling a wooden lever to change pitch. A few years later, French engineer Robert Esnault-Pelterie invented the first true joystick, combining pitch and roll into a single hand-operated control. It even shaped how modern machines are controlled: the military now uses Xbox-style controllers to pilot drones and robots, because they’re instantly familiar to recruits raised on games.

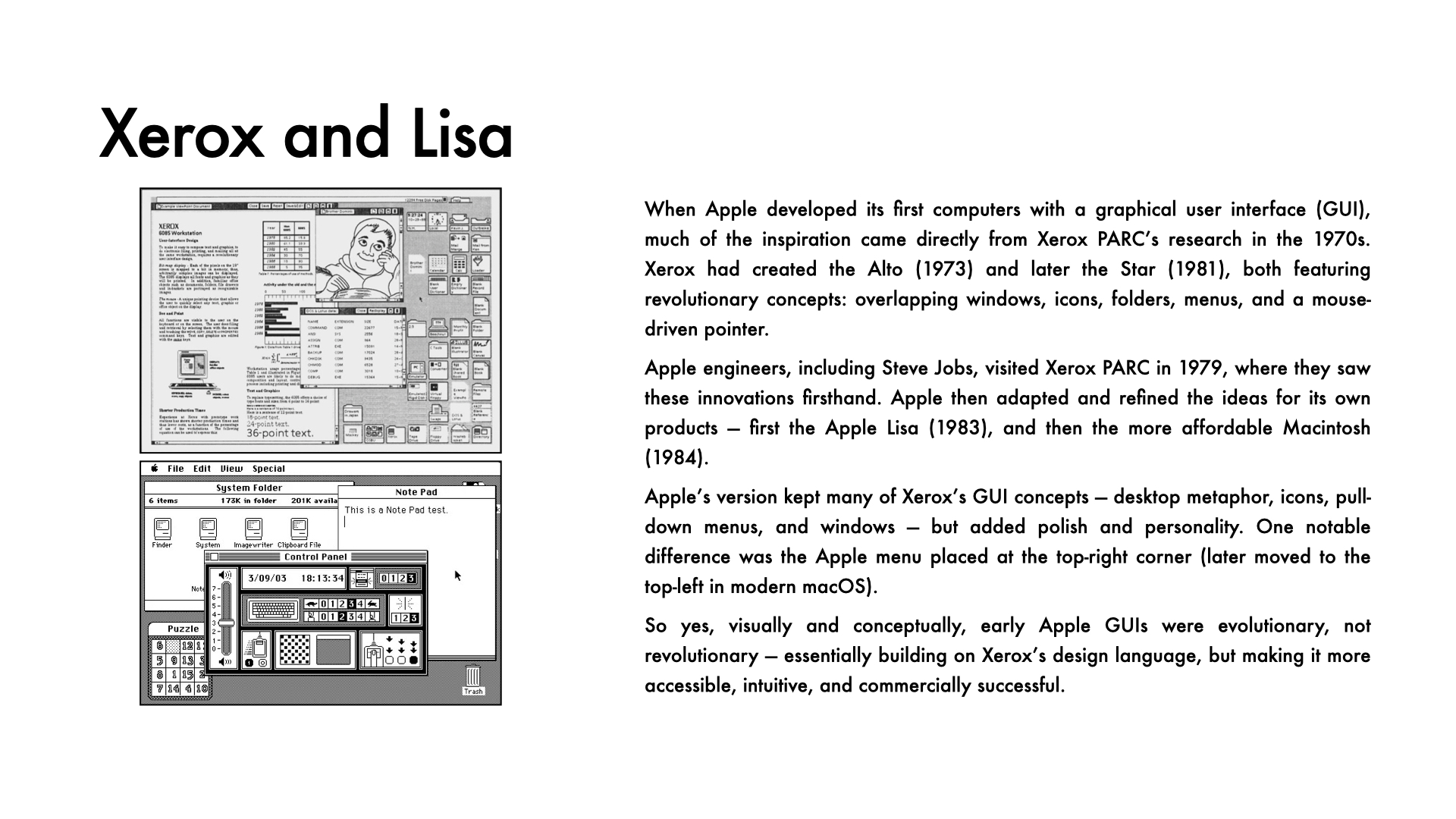

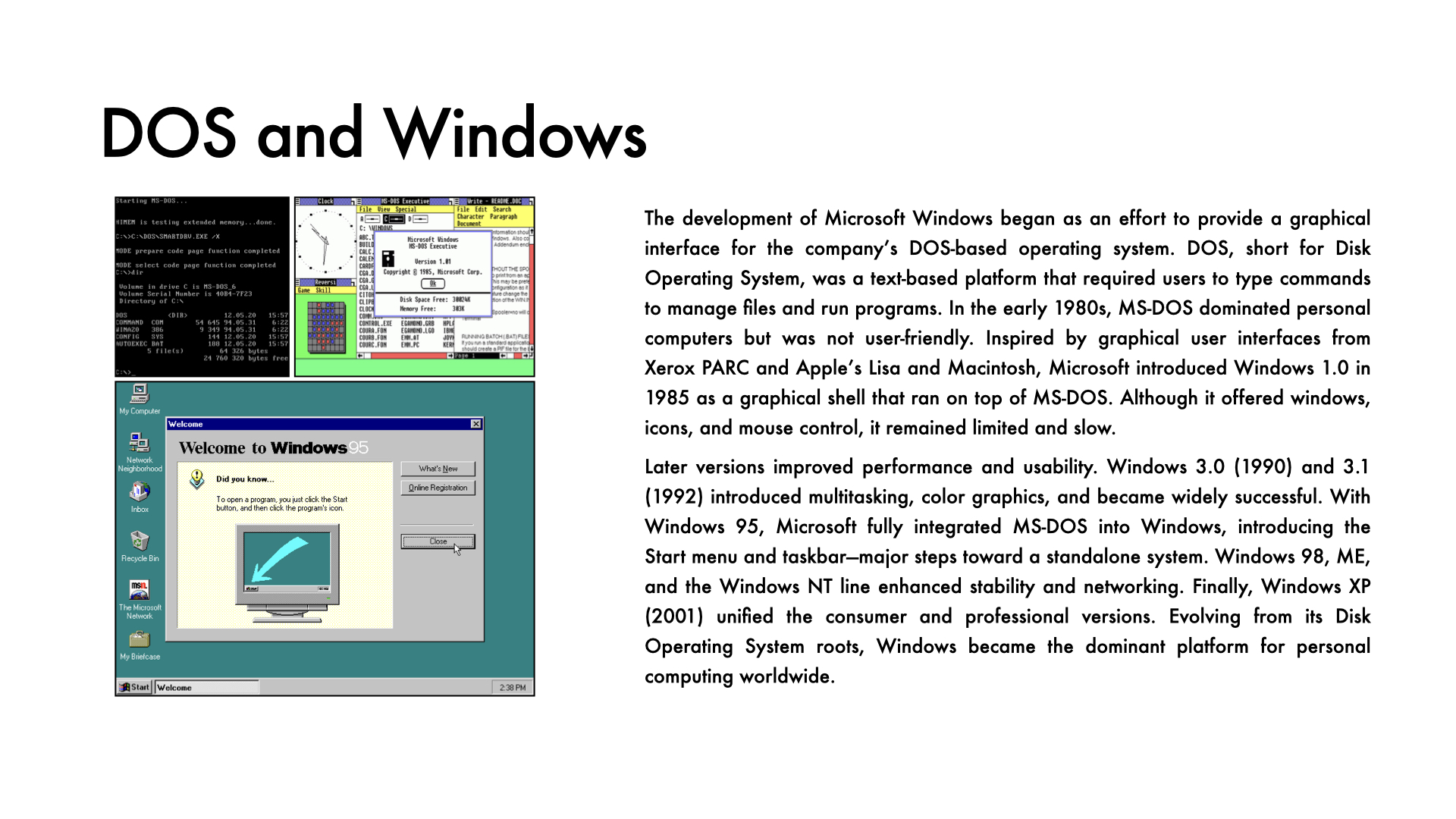

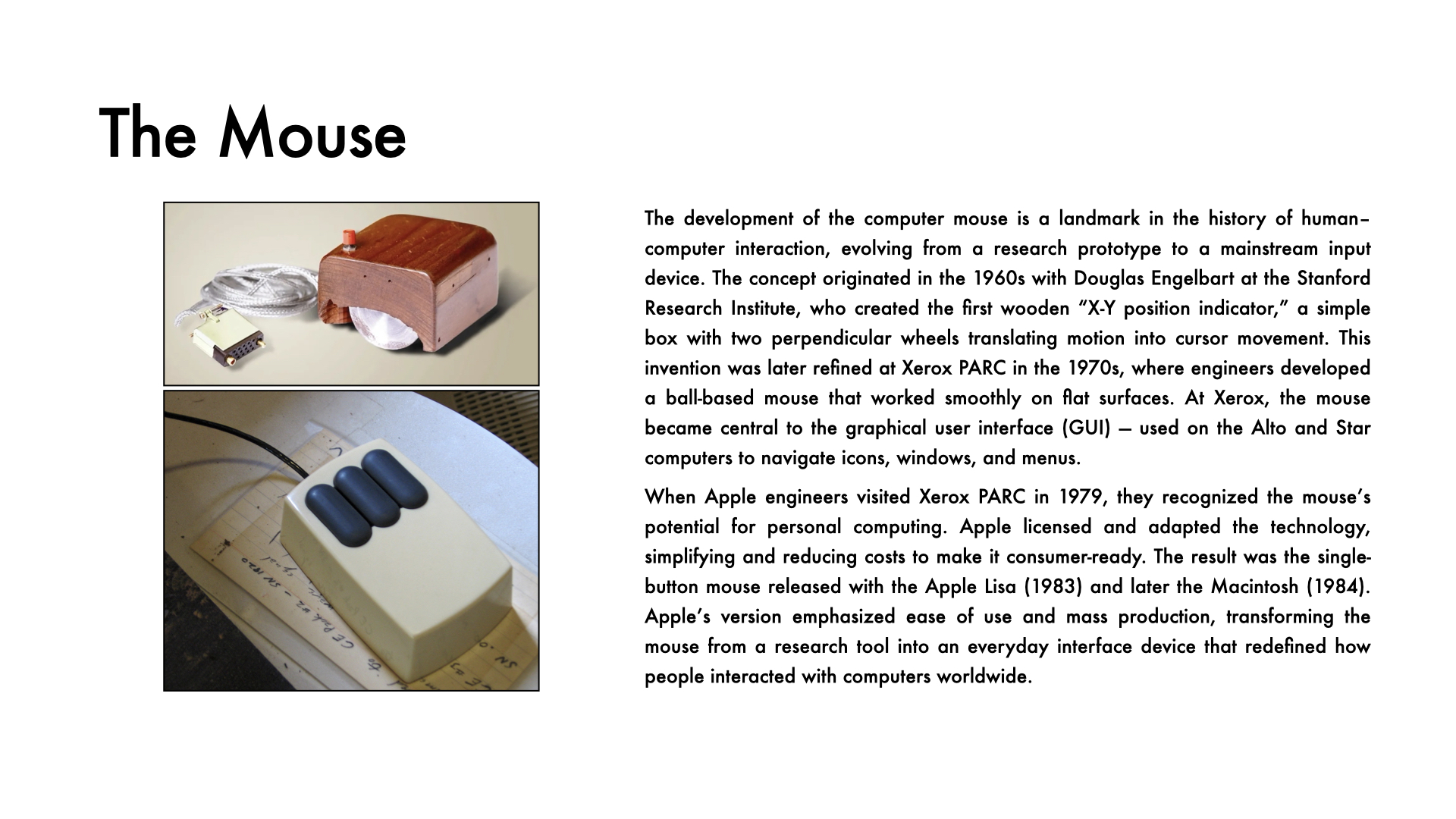

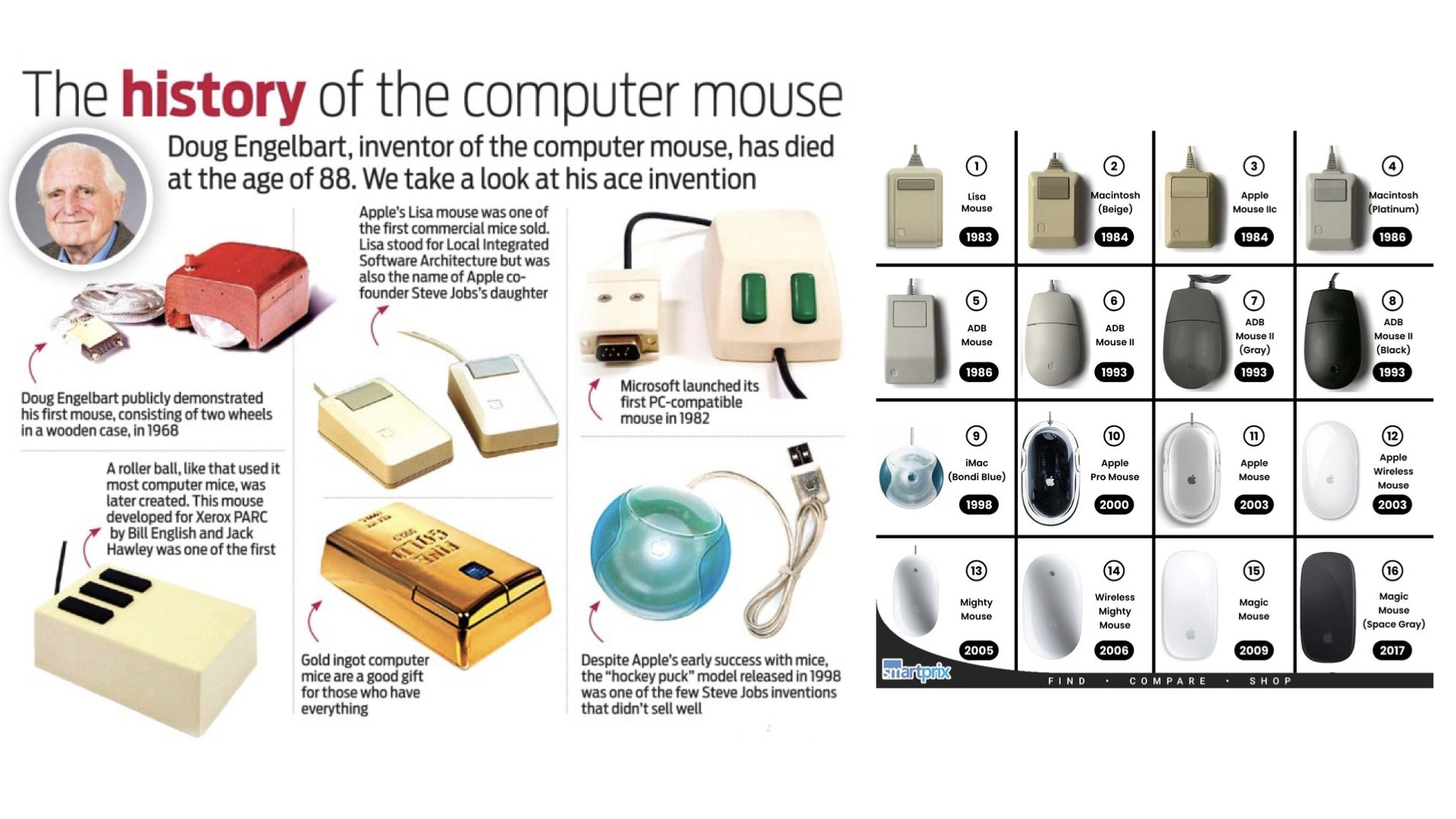

The same principle guided the computer mouse. At Xerox PARC in the 1970s, researchers developed the mouse and the graphical user interface — windows, icons, and menus that visually afforded interaction. Decades later, the iPhone did something similar: it wasn’t the first touchscreen, but it was the first to make touch feel natural — pinching, swiping, tapping — all gestures that afford their actions instantly.

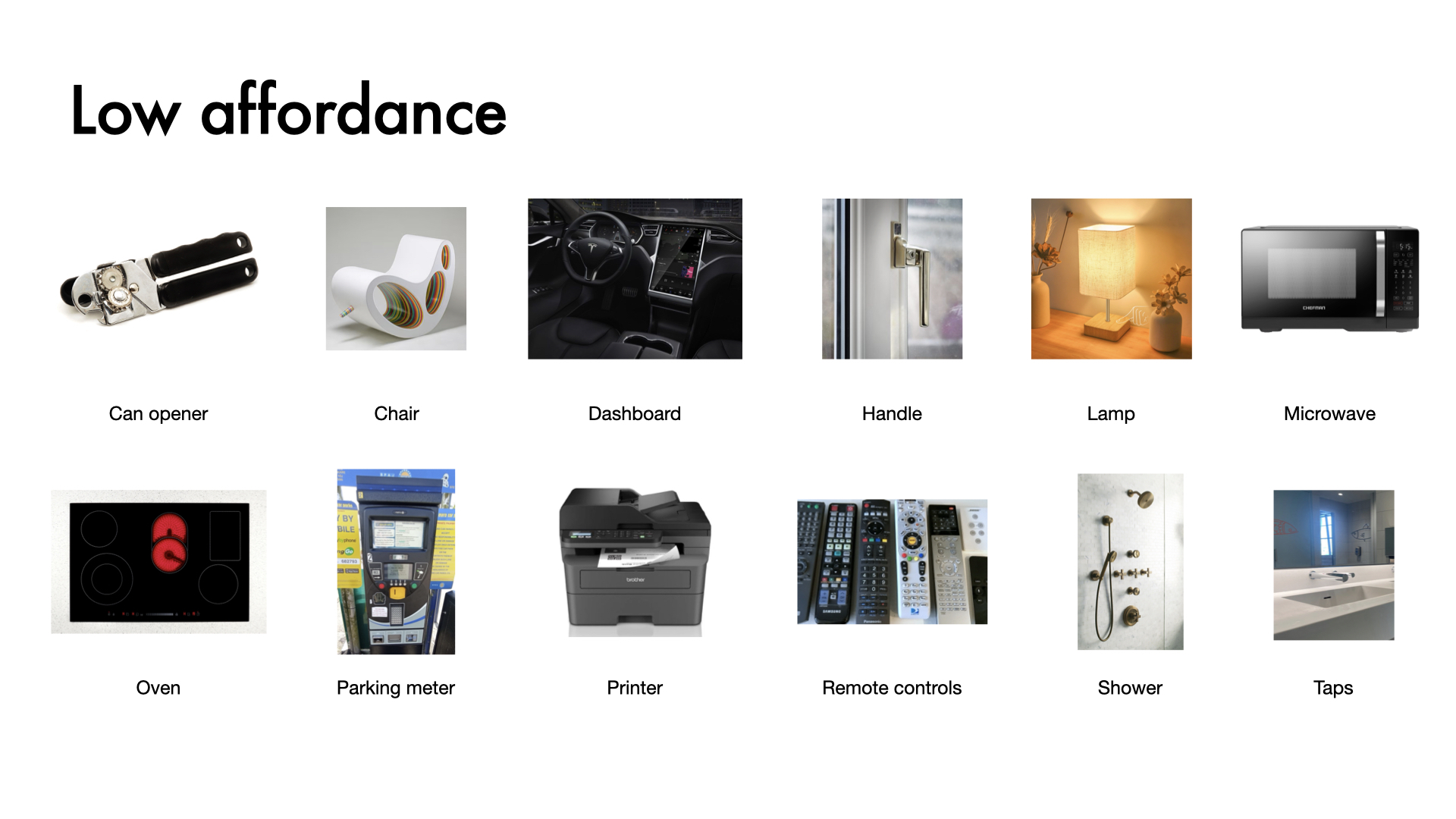

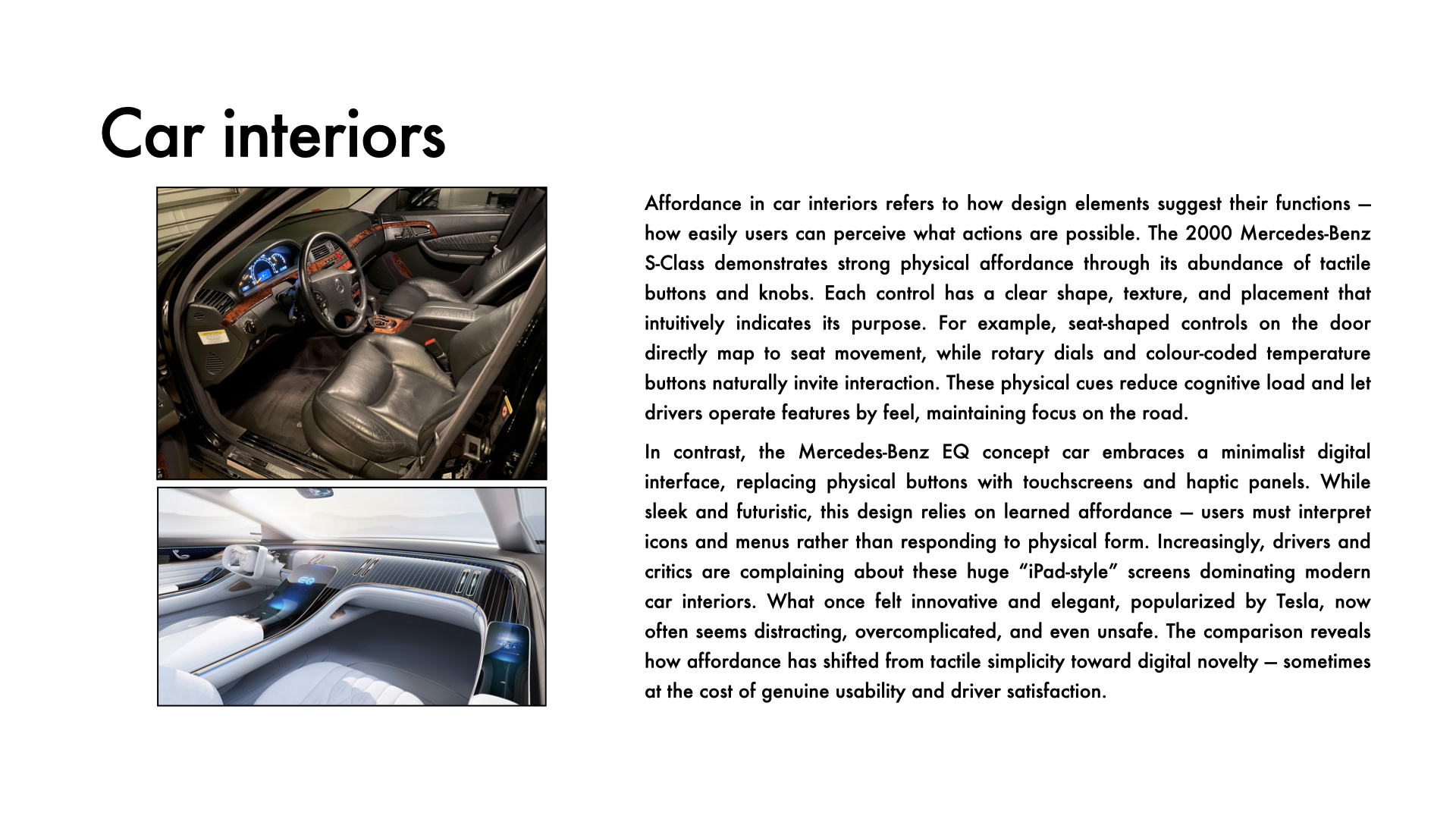

Now compare that to modern cars. Most have replaced tactile knobs and levers with touchscreens — smooth slabs of glass that all look and feel the same. There’s no affordance anymore — just frustration disguised as minimalism.

At its heart, affordance is about communication between human and object. It makes design feel natural, trustworthy, even invisible. And when it’s missing — whether in a Norman Door, a dashboard, or a badly designed app — we’re reminded that good design doesn’t just look sleek. It tells you how to use it.

📽️ Slideshow

📺 Video

🔑 Key Vocabulary

- Accessibility – how easily a design can be used by people of all abilities.

- Affordance – visual or physical clues that suggest how an object should be used.

- Ambiguity – when a design’s purpose or function is unclear.

- Clarity – the quality of being easy to see, understand, or interpret.

- Cognitive overload – when too much information overwhelms the user.

- Consistency – keeping similar controls and layouts across systems.

- Constraint – a feature that limits how something can be used to prevent error.

- Discoverability – how easily users can find available functions.

- Ergonomics – designing for human comfort and efficiency.

- Feedback – a system’s response showing that an action has worked.

- Hidden controls – essential features not visible or obvious to the user.

- Intuitive design – design that feels natural and requires no explanation.

- Learnability – how quickly users can understand and remember how to use something.

- Low affordance – when a design doesn’t clearly indicate how it should be used.

- Mapping – the relationship between controls and their real-world effects.

- Mental model – a user’s internal understanding of how something works.

- Perceived affordance – what users think they can do based on appearance.

- Simplicity – reducing unnecessary complexity in design.

- Signifier – a cue or symbol that indicates possible actions.

- Usability – how effectively and efficiently users can achieve their goals.

💬 Conversation Questions

- Which everyday object do you think has the worst affordance, and why?

- Have you ever struggled to use a device because its design was unclear?

- What’s an example of a product you find very intuitive to use?

- How do clear signifiers improve a user’s experience with a product?

- Why do you think public machines like parking meters often cause cognitive overload?

- Can you think of a design that relies too heavily on hidden controls?

- How do your mental models affect the way you approach unfamiliar technology?

- What’s an example of a design that gives excellent feedback to the user?

- How important is consistency in the usability of everyday objects?

- Which redesign of a common object do you think would improve simplicity or clarity the most?

🌐 Links

- 99percentinvisible podcast – Stick it to 'em

- Time magazine – Why the Computer Mouse’s Inventor Isn’t the Big Cheese

- WIRED.com – This Video Game Controller Has Become the US Military’s Weapon of Choice

- WIRED.com – Touch Controls on Stoves Suck. Knobs Are Way Better

- Apple Insider.com – What Apple learned from skeuomorphism and why it still matters